Yom Kippur 5765 — Your mission in life

Yom Kippur 5765

Rabbi Dr. Barry Leff

“Your mission, Jim, should you choose to accept it…” When I was a kid, I would hear those words coming from the TV, and then sit on the edge of my seat waiting to hear what kind of difficult, no, impossible, mission was going to unfold over the next hour.

Real life is not so simple. We don’t wake up one morning when we turn 21…or 31, or 41, or 51…and receive a tape from God which begins, “Your mission, Barry, should you choose to accept it…” Instead, one of life’s biggest challenges is to figure out just what the heck our mission is.

And I believe that discovering one’s mission in life is one of the most important spiritual tasks a person can undertake. It is an active response to the question of what is the purpose of life.

So what does Judaism say about the purpose of life?

We find the answer by starting at the beginning: the creation of the world. The Torah opens with: In beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. But that’s not the whole story: the Jewish mystical tradition, Kabbalah, elaborates on our Creation myth in a way that has profoundly influenced the way Jews view the meaning of life. Keep in mind that we do not look at these stories as in any way competing with the scientific view of what happened—they work in a different realm, a beautiful tale designed to enlighten us on how God chooses to interact with the world.

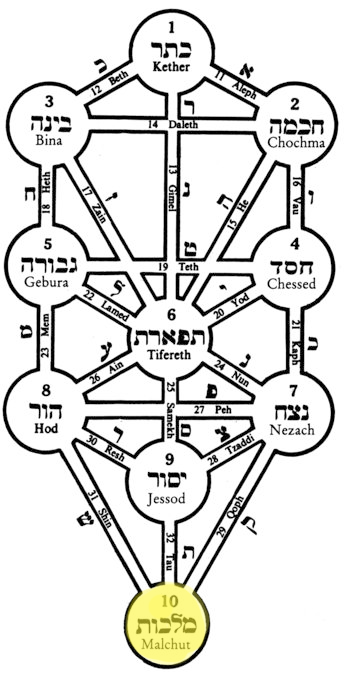

Before the beginning, God filled the Universe. The first thing that had to happen in creation was a contraction: God had to withdraw, concealing God’s self, so that there would be room for the physical world. God then began to emanate into the world, pouring His divine energy into vessels called sefirot, which represent different ways God has of interacting with the world—a bridge between the finite and the infinite. The vessels were not able to contain God’s light—it was too powerful—and the vessels shattered. The remnants of those shattered vessels are the physical world we live in. Yet those shattered shards contain some Divine energy, just as a broken honey jar would still have honey stuck on the pieces of glass. The world, in a sense, was created in a cosmic work accident. Our communal mission is to put God back together again, to restore those slivers of the Divine that have been cast down with the physical. And the way we do that, the way we fix the world, is through doing mitzvot. To the mystics, any mitzvot we do—whether feeding the hungry and clothing the naked, or lighting Shabbat candles and keeping kosher—contributes to “tikun olam,” the repair of the world, the bringing of the holy sparks back to God.

Yesod HaAvodah, the first Chasidic rebbe of Slonim, wrote that each of us has a unique tikkun, a unique healing of the world that we are uniquely qualified to do. It is for the purpose of fulfilling this unique mission that our souls began the long journey downward into our bodies, into the physical world. The mystics tell us that no one else can accomplish our missions: by dint of our uniqueness, those special characteristics that come with our soul being put in our bodies and the things we have experienced in our lives, there is some special thing that each one of us can accomplish that no one else can.

But how do we find that mission? As Po Bronson puts it in his book What Should I do with My Life, “Wouldn’t it be much easier if you got a letter in the mail when you were seventeen, signed by someone who had a direct pipeline to Ultimate Meaning, telling you exactly who you are and what your true destiny is? Then you could carry this letter around in your pocket, and when you got confused or distracted and suddenly melted down, you’d reach for your wallet and grab the letter and read it again and go, “Oh, right.”

One of the people Bronson interviewed for his book actually got such a letter. Choeaor Dondup, who grew up in a refugee camp in southern India, was a 17 year old who had not yet figured out what to do with his life when he got a letter from the Dalai Lama telling him he wasn’t actually Choeaor Dondup, but rather he was the reincarnation of a warrior who along with his five brothers ruled a poor and remote region of Eastern Tibet six lifetimes ago. In that earlier lifetime he founded thirteen monasteries and became the great spiritual leader of the region. It was now Choeaor’s turn to train for this position.

I would not suggest that you go home and wait for a letter. In the Jewish world, we don’t have the equivalent of the Dalai Lama, and I don’t think the Dalai Lama has found any reincarnations of Tibetan warriors among the Jews. Besides, having the answer dropped in your lap would NOT be the Jewish way to address the question of what to do with one’s life. Jews focus much more on questions than on answers.

In figuring out what we should do with our lives, asking the right question is of critical importance. We ask our kids “what do you want to be when you grow up?” And we smile when we hear the usual answers – ballet dancer, astronaut, fireman, actor, rock star. I’m particularly tickled when one of my kids says “rabbi.” But we get so used to hearing the question framed that way by grownups, it’s still that same question we ask ourselves when we get to college: “What do I want to be when I grow up?” And this is the wrong question to be asking.

What do I want? The answer will almost always be a job that is “fun.” A job that is “exciting.” A job that is NOT boring, not ever. And this becomes the impossible dream and can lead to bouncing from job to job as the excitement of each new experience wears off.

We live in an exciting, fast moving world. Email isn’t fast enough anymore: we have to have cell phones and Blackberries and Treos and Instant Messaging so we can be in constant contact. We don’t play chess, we play video games. Instead of thinking about a move for minutes, we react in a fraction of a second. The impact of all of this modern technology is to make us stimulation junkies, easily bored if things don’t move fast enough. And we expect this same kind of stimulation in our work.

The truth, however, is that stimulation is not enough. Stimulation is not enduring. Our mission in life is not to spend the next forty years or so being stimulated. Being stimulated is not the same as being fulfilled. Being stimulated is not the same as making a meaningful contribution to the repair of the world.

In his book, Po Bronson suggests that a better question is “What should I do with my life?” Many of us have a sort of phobia of the word “should.” We don’t want to be told what we “should” do. A good friend of mine told me he always avoided even using the word “should.” Should, he said, was a “religious term,” and as he was not religious, it was something to be avoided like the plague.

Since I’m in the religion business, I have a license to use the word “should.” But even this question, “what should I do with my life,” doesn’t go far enough in the spiritual dimension. It is still focused on “I,” on the “me.” In Po Bronson’s book he gives an example of a young man who enjoyed helping people, and he was good at golf—he realized his perfect job was to help people play better golf! And it launched him on a career working for a golf equipment manufacturer designing things that help people improve their golf game. This young man may have found a worthwhile career—he may even be what the psychologist Abraham Maslow would call “self-actualized,” doing what he has the potential to do—but could that really be his unique mission in the world, his contribution to the healing of the world? He might be happy and feel fulfilled at work, but is that all there is?

Judaism does not teach that God’s greatest concern is our personal happiness and feeling of fulfillment. God isn’t here to serve us, we are here to serve God. There is a goal for each of us to accomplish. A story is told of Rabbi Shneur Zalman, the founder of the Chabad branch of Chasidic Judaism. One time Reb Zalman was in jail on a trumped-up charge. The rav looked quiet and majestic as he sat meditating and praying awaiting his trial. The jailer figured he looked like a thoughtful person, and wondered what kind of man he was. They began to talk, and the jailer brought up a number of questions from scripture which had been bothering him. In the story of Adam and Eve, right after they eat from the tree of knowledge, they get embarrassed, try to cover up with a fig leaf and hide. God calls out “where are you?” So the jailer asked: “How are we to understand that God, the all-knowing, said to Adam, ‘where are you?’” “Do you believe,” answered the rav, “that the Scriptures are eternal and that every era, every generation, and every man is included in them?” “I believe this,” said the jailer. “Well then,” said the rav, “in every ear, God calls to every man: ‘Where are you in your world? So many years and days of those allotted to you have passed, and how far have you gotten in your world?’ God says something like this: ‘You have lived forty-six years. How far along are you?’” When the jailer heard his age mentioned, he pulled himself together, laid his hand on the rav’s shoulder, and cried: “Bravo!” But his heart trembled.

And why did his heart tremble? Forty-six years have gone by, and had he gotten very far in his world, in his mission in the world?

My mentor (or as he sometimes describes himself, “mentor and tormentor”) from my business career, Dr. Abe Zarem, shared with me a great question that his mother used to ask him: “Why were you put in my womb?” Can you imagine your mother asking you this? I suppose it could feel very different depending on the mood she was in when she asked!

This is a much better way to phrase the question. Having a child is a blessing from God. When God put us in our mothers’ womb, God had some reason for choosing to do that. There was some purpose, some mission that God had in mind for us to accomplish. Our challenge then, is to figure out what that purpose is, and to go do it.

For Abe, his answer is “to identify talented people and push them to accomplish more than they otherwise would.” This is a mission that can be accomplished in any number of jobs and any number of settings—and Abe has done just that in a variety ways from mentoring young entrepreneurs he invested in—I met Abe almost 20 years ago—to being generous with his time and advice to young (and not so young) people who are struggling with the question of what to do with themselves. Abe has a unique way of contributing to the improvement of the world.

I’ve grappled with this question myself, and I believe for me the answer is to bring Jews closer to Torah and mitzvot—which will also bring them closer to God. Clearly I hope I am doing this as a pulpit rabbi. But I am also aware that there are other paths, other avenues by which I could accomplish this task.

Identifying the crucial question: “why was I put in my mother’s womb?” is important. But how do we find the answer to the question?

There are some who would dismiss a question like this as a sign of upper middle class Western angst. Poor people don’t get to choose. They are happy to have whatever job they can find to put food on the table and a roof above them. Why worry about ultimate meaning? Why not just go out and get a job and make a living, and be done with it?

Our tradition says EVERYONE—rich, poor, with great gifts or modest gifts—has a contribution to make to tikkun olam. We each have a role to play in making the world a better place. In the book of Deuteronomy it is written, “re’eh, anokhi notan lifneikhem hayom bracha u’klala,” “see, I set before you today blessings and curses.” The Slonimer rebbe taught that figuring out your mission in life, your unique tikkun, and accomplishing it, is the greatest blessing a person can have. It is its own reward. Toiling for 70 years and not accomplishing your mission, or not even figuring out what it is, is the greatest curse. It is to waste your life.

Your life mission—your unique task—does not necessarily have to be working at a job that is overtly altruistic. The world needs people who do the most mundane of jobs. My first Talmud teacher was a Chabad rabbi. When I announced to him that I was thinking of giving up high tech to become a rabbi, he sort of discouraged me: saying, not everyone needs to be a Torah scholar. Some people have the role of making money, which they can give to tzedaka to SUPPORT Torah scholars. This is a model, by the way, described in the Midrash, where it says the tribe of Zebulun were merchants who worked to support the tribe of Issachar who were scholars. And of course secular Israelis support the haredim in the Yeshivas today, but we’ll leave that for another sermon. I don’t think that Chabad rabbi was really trying to raise money from me — he was just stating a simple fact: we can’t all have the same mission, we are not all destined to be rabbis!

But when doing a mundane job, the person who is accomplishing a mission will bring meaning to the task. The story is told of three bricklayers who were asked why they were doing what they were doing. One said for a paycheck. The second said to support his family. The third said “I’m building a cathedral.”

Sometimes we have to try a few different jobs or courses of study before we find the one that resonates, the one that we recognize as the right one. Disaster and failure can often provide the stimulus that one needs to move in a new direction. Many people find their life’s calling in working for organizations like the Cancer Society, or Mothers Against Drunk Driving, after they have been struck with personal disasters. While not all of us encounter such life-changing issues, most of us have had failures on a smaller scale: jobs that weren’t quite right, that weren’t working out the way we had hoped. It can be scary when it happens, but it can also be the time of opportunity.

Six and a half years ago, I was working as VP Marketing for a smallish ($100 million) computer chip company. I had left a very large company six months earlier for a position that in many ways had less responsibility, but I thought I’d be happier in a smaller company. The company had hired me based on my expertise in the cell phone business—they wanted to move into this business because it was much higher growth and much sexier than the mundane timing chips they were making. It turned out the company did not have the products, the technology, or the capability for investment needed to succeed in this new business; in other words, there was nothing I could do for them. It was a bad fit. When it became clear that I should move on to something else, the easiest thing, certainly the easiest thing financially, would have been to take a comparable job in a company that DID have the right technical capabilities. Instead I took a deep breath, and with three kids and a wife due to deliver another in a few days, I quit my job, put the house on the market, and went to rabbinical school.

Which points to one of the biggest potential barriers to accomplishing our life’s mission: success at the wrong job. There is nothing harder than to leave a job where we are basically content and successful, but unfulfilled—where we know we are not living up to our potential, but are comfortable. When we encounter adversity, we really need to make the most of it because it is so difficult to change when things are going well! It is of critical importance to take advantage of the opportunity when a little adversity comes your way.

Some people have an idealistic vision of something they want to do when they are young. They figure they’ll get a “real” job for just a few years to put some money away, and then they’ll quit and pursue the dream. A lot of people go to law school because they want to change the world. They want to protect the rights of the oppressed as a public defender. They want to save the environment. Then they get to law school, rack up tens of thousands of dollars in student loans and take a job with a big law firm, telling themselves it’s just until they pay off the loans. But somehow those student loans turn into car loans and mortgages, and somehow the original dream gets lost. Do you know anyone who had a dream, put it on hold a few years to make money, and went back to it? I only know one such person. It happens, but it is very rare. The message is don’t put your dreams off—as the great rabbi Hillel said, “if not now, when?”

Your life’s mission is not necessarily what you do at a regular full time job. Today’s Torah reading was about Aaron, the Kohen Gadol, the High Priest, and the details of what he did on Yom Kippur. We can’t all be the High Priest, and not every day is Yom Kippur. Some of the most important characters in the Biblical narrative were relatively ordinary people: for example, last week we read the story of Sarah becoming pregnant and giving birth to Isaac—the story of one of the ancestral mothers of the Jewish people. Her mission was to be a mother, and a role model. It could well be that you fulfill your most important work as a volunteer, or on a part time basis. I’ve known successful people who do not derive great satisfaction from their careers, but rather from their outside activities. Rashi, perhaps the greatest Torah scholar who ever lived, whose light still shines for anyone who studies Torah or Talmud, did his life’s major work as a “part time” task—his income came from his work as a wine merchant. Or more likely his Torah work was his full time work, and his part time work as a wine merchant paid the bills. But the point is the same. Don’t confuse your main purpose in life with your job title.

Today is Yom Kippur. The Day of Atonement. As we reflect on our year and the things we are asking God to forgive us for, we shouldn’t be content with recounting the sins we have committed and what we have done or will do to correct them. We also should consider the curse of not living up to our full potential. When Rebbe Zusya was dying, his students found him crying. They asked him what was the matter; “how could you be worried about your death? Surely you’ll go to the world to come, you’re so holy, you’re like Moses!” Rebbe Zusya said, “when I die and am brought before the heavenly Beit Din, I’m not worried that they will ask me ‘why weren’t you more like Moses?’ I’m worried they will ask me ‘why weren’t you more like Zusya?’”

G’mar Chatimah Tovah.