Emor 5766 — Intermarriage

This week’s parsha orders the Kohen, a priest, not to marry a divorced woman or a convert. The Conservative movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards decided that encouraging endogamy (in-marriage) is so important it was worth overturning a commandment in the Torah.

Back in 1950 the intermarriage rate was 6%. In 2000 it was around 50%. What changed? This week’s D’var explores the issue of intermarriage and our response as a Jewish community.

Once upon a time, it was the role of the father to find a bride for his son, or to make a match for his daughter.

This week’s Torah portion puts limits on who a Kohen, a priest, can marry that many of us in the modern world would find difficult to accept. The Torah says “A widow, or a divorced woman, or defiled, or a harlot (someone who had pre-marital sex), these shall he not take; but he shall take a virgin of his own people to wife.”

Nowadays, of course, people make their own matches. We don’t so often marry because of political alliances or such considerations. A couple marries because they fall in love.

This week’s Torah portion would tell us that if a Kohen, a man descended from the priestly class, falls in love with a divorced Jewish woman they can’t get married—at least not in a religious setting. I have to admit I would have a hard time as a rabbi telling a Kohen who fell in love with a divorced Jewish woman that I can’t officiate at their wedding. I’m sure such a conversation could lead to a lot of bad feelings.

Fortunately, I wouldn’t have to tell them no. The Conservative movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards has ruled that it is permissible for a Conservative rabbi to officiate at such a wedding. The thinking in the opinion authorizing this shows that it is basically a response to intermarriage: we are so happy when two Jews want to marry each other, we don’t want to put a barrier in their way. Rabbi Arnold Goodman’s teshuva “Solemnizing the Marriage between a Kohen and a Divorcee” says that the times we live in – times when there is both a high divorce rate and a high intermarriage rate we need to encourage Jews who want to marry each other. If we followed this particular teaching of the Torah, Rabbi Goodman said we could drive the couple away from Judaism, leading them to have a civil ceremony and abandoning the unwelcoming synagogue.

The decision in the ruling was not based on the fact that nowadays we don’t see divorced women as “impaired” compared to their non-divorced sisters – but rather on a concern to support in-marriage in a time of demographic challenge.

The Law Committee said that encouraging IN-marriage – encouraging Jews to marry each other – was so important, it was worth overturning an explicit commandment in the Torah.

It’s so important because in modern times – in the wake of the Holocaust which led to the loss of a third of the world’s Jews, and assimilation which is causing the loss of nearly as many Jews as we lost in the Holocaust, we are concerned about Jewish survival – about our critical mass as a people. How can we fulfill our mission of being a “light to the nations” if we are not a nation ourselves? And on a personal level, most of us don’t want our children to be the ones to break a chain going back to Moses and Mt. Sinai.

The verse from this week’s parsha only applies to Kohenim. So that got me to wondering: where does commandment for endogamy, in-marriage, for the rest of us come from? What passage in the Torah commands us to marry only other Jews?

I’m slightly embarrassed to admit, that despite years of studying Torah very carefully, I was actually surprised to find that this commandment does not appear in the Torah. Nowhere. It’s a rabbinic commandment, although it is connected to a verse in the Torah.

Deuteronomy chapter 7 tells us how we supposed to relate to the 7 nations which the Torah says God has cast out before us (the Hittites, and the Girgashites, and the Amorites, and the Canaanites, and the Perizzites, and the Hivites, and the Jebusites), said to be “seven nations greater and mightier than you;”

The Torah commands us to strike them, destroy them, make no covenant with them, show no mercy to them; Deuteronomy 7:3 says “And you shall not make marriages with them; your daughter you shall not give to his son, nor his daughter shall you take to your son.”

The Talmud (Avodah Zara 36a) tells us Biblically this only applies to those specific seven nations. The arguments between Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai in the Talmud are legendary. However, in this case they agreed: they extended the decree to other nations as well, mandating endogamy for Jews. The commandment for Jews to marry only other Jews goes back 2000 years, to the very dawn of rabbinic Judaism.

Why did the rabbis Hillel and Shammai impose this requirement?

We find out by looking at another passage in the Talmud, Yevamot 76a, where we are told that an Israelite with “crushed stones” – in other words, a man who is not fertile and cannot have children – is allowed to marry a non-Jew. Why is a man with crushed stones given this special dispensation?

It’s because the reason there was a concern about marrying a non-Jew was that the children would grow up to be idol worshippers. In other words, 2000 years ago, the rabbis were worried about ensuring Jewish continuity – just like we are concerned today. They decided we needed a rule requiring Jews to marry within the tribe – and that has been the law for the last 2000 years.

I spoke about intermarriage in a sermon a few months ago, and I expressed my support for this rule. If anything, we need it even more today than ever – ours is a generation that has witnessed the tragic loss of 1/3 of the world’s Jews. We need to replenish our numbers if we are to remain viable as a people.

Unfortunately, this is a very difficult rule to enforce in 21st century America.

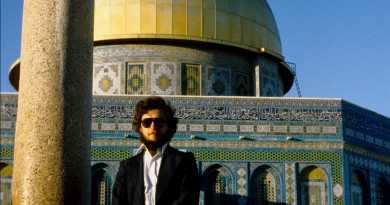

This past week I attended a conference in Berkeley, California. It was a gathering of rabbis from Conservative congregations from all over the United States to discuss the issues surrounding how we deal with the intermarried families in our communities.

I would like to share a few interesting things I learned at the conference.

We in Toledo are in a little bit of a “bubble.” Less than 10% of our over 400 members are intermarried families. How we involve non-Jewish family members in simchas is an issue that I am discussing with the ritual committee, but it’s not something that comes up with the majority of b’nei mitzvah.

It’s been said that where California goes, the rest of the nation follows, just ten or fifteen years later. Maybe in Toledo it’s 20 years later. But some of the things I heard from colleagues in California made me realize the magnitude of this issue is far greater than I would have thought from the vantage point of Ohio.

One Congregation in Marin County surveyed children in their preschool. 97% of the kids come from intermarried families – and it’s NOT because the non-intermarried are at Chabad. 97% !!

At this same congregation – a very traditional Conservative congregation in terms of liturgy and ritual – a woman who was very active in the shul, one of the regular Torah readers, someone who occasionally leads prayers, a woman with a kosher home who observes the Sabbath married a non-Jew. Even observant people in California don’t seem to feel there are any problems with intermarriage.

I lived in California for over twenty years, but I was frankly shocked by the statistics and by the stories. California may be a different world, but I don’t think we can ignore what’s happening elsewhere – we need to understand the younger generation, which is represented by some of the things we see happening in California, where more of the younger generation is living.

A demographer, Sherry Israel, spoke with us and helped explain WHY these things are happening.

It’s not because we are failures at encouraging endogamy, in-marriage. In fact our roughly 50% intermarriage rate is far better than any other ethnic group. 75% of descendants of Japanese Americans marry non-Japanese Americans—even though I’m sure many of the parents want to keep their Japanese heritage alive in their descendants. America is a society with fluid identity.

Back in 1950 the intermarriage rate was 6%. In 2000 it was around 50%. What changed?

What changed is a combination of where we live and who we are.

Who we are shows definite generational differences. There are the traditionalists, born before 1945; the baby boomers born from 1946-1963 or so; and the “Gen X’ers” born 1964 to 1980.

The Traditionalists mostly grew up in Jewish neighborhoods. They got their Jewish identity from hanging around with Jews. They married other Jews because that’s who they met. My father and his sisters grew up knowing they were Jewish without having to do a lot about it – they lived in a “Jewish bubble” in New York City where most of the people they met and hung out with were Jewish.

I’m not blaming them for lacking clairvoyance, but the Traditionalists made one big mistake: they assumed their kids would be Jewish just like them. They assumed that their kids would also learn to be Jewish through osmosis.

However, they moved to the suburbs where it’s no longer a Jewish neighborhood and their kids no longer only hang around with Jews. “Oops!”

Mobility is a hallmark of American life. Even here in Toledo, which is a pretty stable place compared with somewhere like Colorado or California, about half of us are from somewhere else, and among the older generation most have children living somewhere else.

Our mobility has been from places with dense Jewish life – like New York – at one time ¾ of America’s Jews lived in the Northeast – to places with less dense Jewish life. Less dense not only in terms of fewer Jews, but less dense in terms of Jewish community, restaurants, culture, classes, etc.

The result: much weaker Jewish identity among a lot of the boomer generation when compared with the generation before. So what happened? Statistics and the facts of life hit us in the face, and the Jewish community reacted very strongly and very positively. We developed programs like Camp Ramah, USY, we improved our Sunday schools, we built a huge number of Jewish day schools. Some philanthropists launched the Birthright program to give every Jewish youth between 18 and 26 a free trip to Israel. All to try and instill that sense of Jewish identity in our young people who no longer get it by osmosis.

As a community we have made and continue to make big efforts to instill a strong Jewish identity in our children – because we believe if they have a strong Jewish identity they will want to marry other Jews who will share that with them, and the Jewish people will continue to be around to contribute to the betterment of the world as a people.

For the younger generation – “Gen X” – mobility is not only geographic, but also in their personal identity. The younger generation is comfortable with having multiple identities – perhaps partly because so many of them come from families where the parents come from different ethnic or religious backgrounds than each other.

The baby boomers were the generation that championed civil rights and feminism. We were successful – our children believe what we taught about everybody being equal. We’ve now created a problem for ourselves: a problem of language. With the younger generation we cannot use the language of exclusivity – it sounds contrary to all those other lessons we successfully imparted! How can we preach how everyone is equal and then tell them they have to marry Jews?

Language is very significant. We had a presentation from a young woman whose father is Jewish and whose mother is French and not Jewish; she always identified herself as French and Jewish. She was crushed when she had a Jewish boyfriend whose grandmother didn’t want to meet her because “she wasn’t Jewish.” Her reaction was “What do you mean I’m not Jewish!!”

She later married someone else—also Jewish—and got involved with a Conservative synagogue. By our standards, she needed to go to the mikvah to be considered Jewish – technically a conversion. When confronted with the language of “conversion” it was difficult for her, because she considered herself already Jewish. It would have made her Jewish journey easier if the rabbi had affirmed her Jewish identity, and said the mikveh was an “affirmation,” a technicality, NOT a conversion.

I’m pleased to see smart colleagues are working on solving the language problem, trying to find language and ways to reach the younger generation.

California may be extreme, but even here in Toledo we are not isolated from intermarriage. How many people here have a close family member – parent, sibling, child or grandchild – who is intermarried? (It was about half…)

There is a lot more intermarriage in our community than we admit. We may not have a huge number of intermarrieds in our congregation, so we don’t think about it so much. But that’s the problem—they are not joining. Often when I do a funeral I meet the children who have “left the fold.” There are a lot of them around.

Our response cannot simply be “don’t intermarry.” One colleague said that’s as effective as saying abstinence is the only option for birth control for unmarried people. We need a more nuanced approach.

We need a more nuanced approach because not every intermarriage is the same. Being intermarried does not automatically mean that the person has turned his or her back on Judaism.

Both the Reform movement and the Conservative movement have embarked on programs to encourage non-Jewish spouses to convert – apparently believing that this is the way to ensure Jewish identity.

It sounds good – and I’m a strong believer in encouraging conversion. But I was very surprised to learn some statistics which suggest that conversion is not actually that important.

What’s important is getting intermarried couples to join a synagogue, whether or not the non-Jewish partner converts.

A 1995 study by the Jewish Federation of Boston showed intermarried Jews who belonged to synagogues lit Hanukah candles, observed Shabbat as special and donated to the Federation at nearly the same rates as synagogue members married to Jews by choice, and at much HIGHER rates than in-married Jews who did not belong to a synagogue.

Intermarried families that joined synagogues generally raised their children with unambiguous Jewish identities; it was even stronger when the non-Jewish partner converted. But the biggest difference came with joining a synagogue.

There are intermarriages where the non-Jewish partner pulls the Jew away from his faith and the children are lost to the Jewish people. My brother intermarried and I have nieces and nephews who are Catholic. I talked with a friend in California who is pained that his grandchildren are being raised Catholic; his son and daughter-in-law know better than to invite him to things like Confirmation and suffer the embarrassment of him turning them down.

But there are also intermarriages where the non-Jew pulls the Jew closer to Judaism. We have a few of those here in our congregation, where the Jew is coming to my classes because his non-Jewish partner nudged him in that direction. And of course I ended up becoming a rabbi because Lauri decided to convert, and I was inspired to study with her.

To treat all intermarriages the same is a mistake – we need a more nuanced approach. At the conference they proposed new language – that we call Gentiles who support a Jewish family “Kerovai Yisrael,” a term which means both relatives and close to. A positive term. Someone at the conference told me a Buddhist told him that we Jews have great chutzpah, we’re less than 1% of the population of the world, yet we define everyone else as “non-Jews.”

Kerovei Yisrael are welcome in our synagogue, just as Gentiles were welcome in the Temple. This week’s Torah portion tells us that Gentiles could offer sacrifices to God at the Temple – “Whoever he is, of the house of Israel, or of the strangers in Israel, that will offer his offering for all his vows, and for all his freewill offerings, which they will offer to the Lord for a burnt offering.”

I agonized a bit over whether I should discuss this subject today, our 8th and 9th grade Shabbat. I asked myself whether some of the parents might get upset with me for discussing this topic. Some people are afraid of being too welcoming to intermarried families. They are afraid that if we are too welcoming to intermarried couples, our children will get the message that intermarriage is OK. They will get the message that we don’t care. There are people who feel that parental disapproval and shunning by the community are powerful tools for ensuring in-marriage.

In the end of the day, I decided to go ahead and discuss the subject today because I don’t buy that argument. In the movie “Keeping the Faith,” one of the central characters is a rabbi, played by Ben Stiller. He has a brother who intermarried; the mother, played by Ann Bancroft shuns the intermarried brother—refuses to speak to him for two years. But later, when she is in a hospital bed, she confides to the rabbi son “I made a mistake.” She acknowledged she cannot control her grown children’s lives.

So to our 8th and 9th graders, let me be clear: we want you to marry other Jews! That’s why we spend so much effort on giving you a Jewish education and making sure you meet other Jewish kids at places like USY or Camp Ramah. We want you to continue the chain.

At the same time, however, in a world where two out of three marriages involving a Jew is an intermarriage, one of our missions needs to be to figure out how to be welcoming to non-Jews. And, as one of my colleagues said, “maybe if we figure out how to be welcoming to non-Jews, we’ll figure out how to be welcoming to Jews!!!”

Shabbat Shalom

The Jerusalem Post ran an article about the conference I attended. You can see it at:

http://www.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?apage=1&cid=1145961381490&pagename=JPost%2FJPArticle%2FShowFull

Reb Barry

Intermarriage is something that seems to happen by race and religion. On one hand it is good by thinking we will get along better with the other religion across town, but then in such a small group in the world like Jews, too much assimilation can decrease the numbers by dilution. It seeems like every small group, like say Apache Indians, has similiar problems. It definately is an issue that has to be addressed before adolescence when the hormones rage at full power.