Remembering 9/11

At 7:00am California time on September 11, 2001, I was at home in Los Angeles, still in bed, when the phone rang. It was my mother, calling from Denver: “turn on your television, something terrible is happening in New York” were all the words she could choke out. Confused, we got up, turned on the TV, and like the rest of America watched in dumb-founded silence at what was happening. We watched in disbelief as first one, and then the other tower came crashing down.

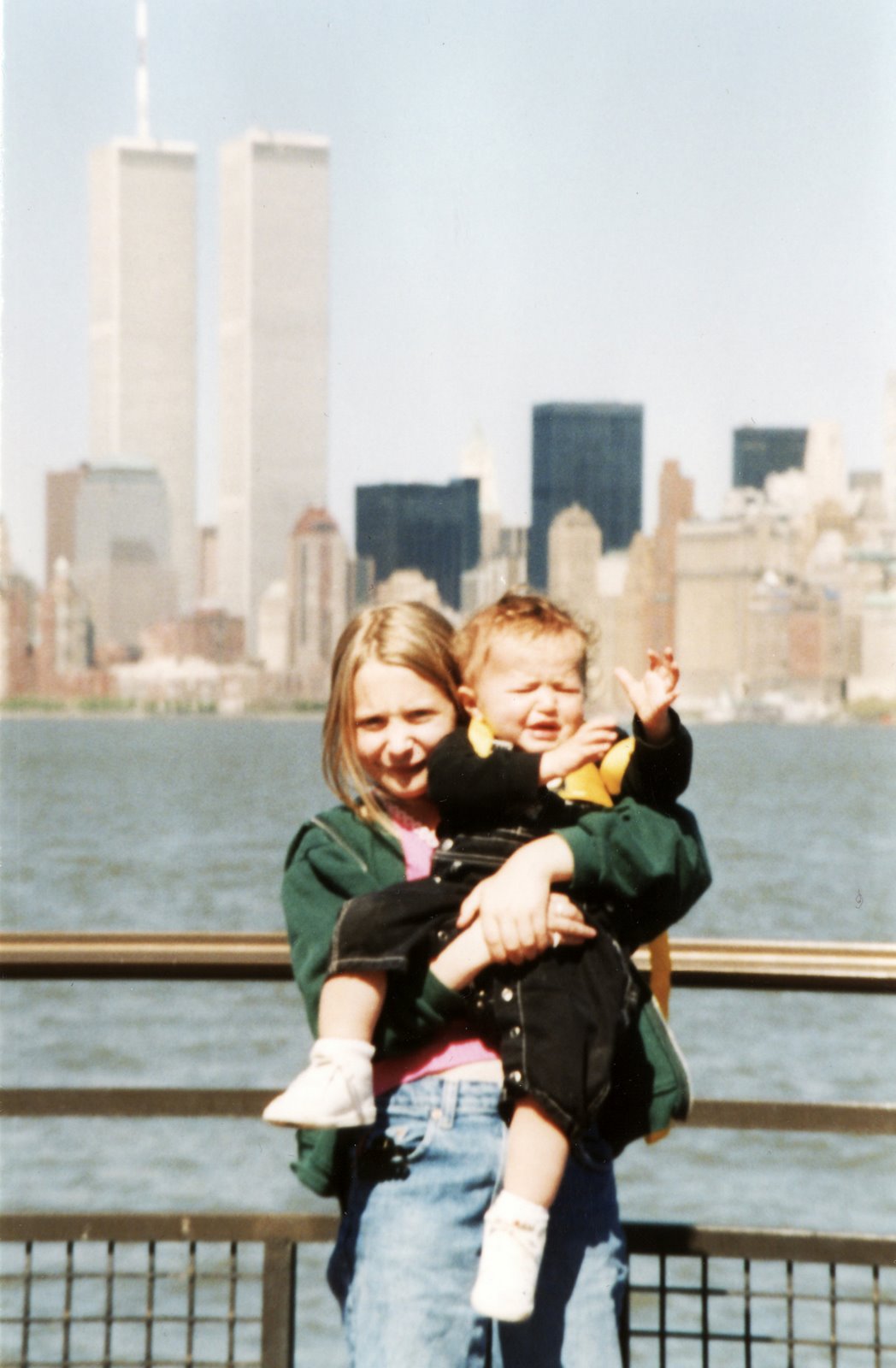

It was the first day of school, a special day in fact, the first day of kindergarten for one daughter, the first day of pre-school for another. Do we keep them home? We decided it would be better to bring the kids to school, a five-year-old and a three-year-old were not going to comprehend what was happening. The baby in the picture is the daughter who was five on that day.

Most of the other parents had come to same conclusion we did. We arrived at school and there was a sense of cognitive dissonance: young children running around, smiling, excited by the first day of school; parents silent, looking shocked and concerned. We went home and spent the rest of the day in shock, like all of the rest of you, glued to the television, watching the same unbelievable images over and over.

The world has not been the same since; a “War on Terror,” a war in Afghanistan, a war in Iraq, wars that are still not fully concluded. A sense of security destroyed. Good people all over the world shaken. Security everywhere we go, a loss of civil liberties and increased government surveillance on all of us, all in the name of preventing another horrific attack.

In all likelihood there will never come a day when we can simply declare victory in the “War on Terror,” which more accurately is the”War on Islamic Extremists.” There will be no signing surrender documents around a large table. The killing of Osama Bin Laden was a major milestone for getting closure to the events of 9/11. Yes, there have been additional terrorist attacks, but nothing on the scale of 9/11. I suspect the War on Islamic Extremists will simply fade away; it will recede in our consciousness as we go on with our lives, accepting as necessary security measures we once lived without.

In memory of that day ten years ago, I append below the sermon I gave at Congregation Bet Shalom in Tucson, Arizona on Rosh Hashanah that year. May we all continue to work together to bring about a world of peace and harmony, to restore the inner security and serenity that was shattered by those events of ten years ago. May we remember those who lost their lives on that day ten years ago, and pray for their souls, and pray for the loved ones they left behind.

Reb Barry

You can also see some remarks I gave at a 9/11 commemoration five years ago by clicking here.

Rosh Hashanah, 2001

On Tuesday, September 11 our lives changed.

We continue to struggle with the confusion of feelings and questions we have. We feel pain, we grieve, we are sad, we are angry, we want justice; some would add revenge. We want to know who, and why, and how. We want to know whether such a thing could happen again. We want to know what our government’s reaction is going to be. We want to know if we can ever feel safe again.

I had originally planned to speak about Israel today. I was going to talk about how some of my experiences in Israel during the last year had shaped my views on how to respond to the situation there.

Obviously, as concerned as we remain about Israel, the events of last week have overwhelmed our ability focus on other things. Yet despite the obvious political connections, the events of last week have another profound connection with Israel. My family and I have recently returned from a year of living in Israel. We know what it feels like to live with the stress of being under attack. Now all of you, and all Americans, have a taste of what it feels like to live in Israel. To live in a place where your life is profoundly altered by cowardly terrorists. I don’t need to describe what it feels like to make phone calls to find out if your loved ones are OK after hearing of a suicide bomber: many of you have had the tension of that experience yourself. I suspect that there will not be nearly so many American calls for “restraint” after a suicide bomber attacks Israel. There have already been reports that the US government is reconsidering its policy against assassination of terrorists.

How do we make sense out of these events? How do we recover our sense of equilibrium? How do move ahead? Last night I spoke about how we cannot blame God for this tragedy. It is pointless to ask how God could allow this to happen. God gave us the most precious possible gift: free will. He gave that gift of free will to all of us, including those who committed this horrible crime against us and against humanity. In last week’s Torah portion it says “I set before you life and death, choose life.” We choose life—they choose death.

As Jews we turn to God and we turn to our tradition at a time of tragedy like this. We need some help, some guidance, in how to deal with tragedy. In a little while we will recite the Musaf Amidah, which contains the famous medieval prayer of Unetaneh Tokef. The most famous line of Unataneh Tokef, which we sing together, and which we have embroidered on our Torah reading table cover at Bet Shalom, proclaims “Teshuva, tefila, and tzedeka–repentance, prayer, and deeds of kindness–can remove the severity of the decree.”

Note that it does not say “change the decree.” It says remove the severity of the decree. What has been decreed, has been decreed. What has happened has happened. We cannot pray hard enough and find that it was all just a bad dream, and see the buildings back in place and lives restored. One of the most horrible things we could imagine has happened. It may have looked like a bad action movie, but it was real life.

However, our actions can remove the severity of the decree. We can find a way to deal with it. We can find a way to ease the pain, a way to help ourselves recover and a way to help others.

I’m going to address each of the three actions—repentance, prayer, and deeds of kindness—moving from the inside out, from the most personal and individual to the most communal.

The most personal, individual action can be prayer. Yes, we come together as a community to pray, but you can pray alone. When you pray you come before God as an individual, using either your own words or the words in the siddur, or a combination of the two.

Last week on Tuesday I found myself unable to pray in the morning. We are commanded to pray three times a day, and I do my best to fulfill this commandment and pray three times a day. Yet last Tuesday I found myself absolutely unable to pray. The pictures I saw on TV, the implications of what I was seeing, was simply too shocking, too mind-numbing, too completely absorbing. I could find no words, in my heart, and I was sure I wouldn’t have found them in the siddur, to express what I was feeling at that particular moment.

In the Talmud we are informed that you should not pray if you cannot have the proper kavvanah, the proper focus. Later authorities have said that we don’t know how much or how little is enough, so to be on the safe side we should always pray even if we think we don’t have enough kavvanah. In general I agree with this rule; however, last Tuesday morning, there was no doubt in my mind whatsoever that I did not have the concentration required to pray.

By later in the day, after some of the initial numbness and shock wore off, that feeling had changed completely. Instead of feeling I couldn’t pray I felt I needed to pray, and I needed to pray together with other Jews. I went to a minyan in my neighborhood in Los Angeles, and found many others who felt the same way—a place where we sometimes struggle to have ten Jews together for a minyan was filled with Jews who needed to come together to pray. When we recited Mourner’s Kaddish, we all rose to recite Kaddish on behalf of thousands of people killed that horrible day. We were all in a type of mourning, and praying together was very comforting.

As the week has gone on, I have found that at different times certain of the words that are so familiar have suddenly jumped out at me with new images attached to them. Praying with the siddur can help us find words to express what we feel. Sometimes we find that King David was able to say it better in a psalm than we could say it ourselves.

Sometimes the words in the liturgy move us to think about the situation. In Psalm 30, which we recite every morning just before Baruch Sheamar, it is written: “I will extol you, O Lord; for you have lifted me up, and have not made my enemies rejoice over me.” I was troubled when I recited this verse one morning last week. I read “have not made my enemies rejoice over me,” and I couldn’t help but think of the images on television of Palestinians handing out candy and rejoicing when they saw the pain and destruction in America. Yet this forced me to think a little further, and remind myself that God did not cause my enemies to rejoice. The enemies were rejoicing because of an act of Man, not an act of God. And God has lifted me up, because I have been able to find some measure of comfort in turning my heart to God at this difficult time.

King David was no pacifist, and his battle cry, expressing our anger, can also be found in the Psalms. The Psalm for the day on Wednesday—the day following the attack—is Psalm 94, which starts out with the cry “God of vengeance, Lord, God of vengeance appear!” The Psalmist had feelings just the same as ours: the end of the psalm proclaims “They gather themselves together against the soul of the righteous, and condemn the innocent blood. But the Lord has become my fortress; and my God, the rock of my refuge. And he shall bring upon them their own iniquity, and shall cut them off in their own wickedness; the Lord our God shall cut them off.”

In addition to finding inspiration in the siddur and in words of Torah, we can simply cry out to God in our ways and in our own words. Rebbe Nachman taught that it is good to pour out your heart to God, like you would to a good friend. You don’t need a book in your hand and you don’t need to understand Hebrew to be able to pray.

We Jews are often uncomfortable with spontaneous prayer. We are so accustomed to our fixed, and lengthy, liturgy that we sort of automatically assume that praying is something we do with a book in our hands. The book is there to be a tool, an aid to prayer, not a barrier. One of the most moving prayers in our scripture is also the shortest. When Miriam was stricken with tzuras, a terrible skin condition, Moses did not recite a lengthy formula. He simply poured out, “El na, refa na lah.” God, PLEASE heal her.

Similarly at times like this, we need both kinds of prayer. We need those fixed prayers and beautiful liturgy where we can find passages that move us or comfort us; and we also need to make that individual heartfelt pouring out to God. Please God, take care of the souls of those killed and comfort their families.

You may wonder at finding “teshuva,” or repentance in the list. Most of us would not subscribe to the theology that we are somehow personally responsible for all the bad things that happen. On one level, we do have a significant responsibility: we have failed to create the kind of world where such things cannot happen. We have failed to eradicate evil—whether through love and example, or weapons of war, we have not yet succeeded in ridding the world of evil. We also have not until now taken the expensive and inconvenient steps needed to add to our security against terrorists. We need to redouble our efforts to eradicate this evil from our midst.

However, teshuva means more than repentance. Teshuva literally means return. Classically understood as a return to God; however teshuva can also be a return to our loved ones.

Some of the most heart-wrenching tales from this terrible week have been the final phone calls. People on hijacked planes calling to tell their loved ones what was going on. Tales of heroism in the skies as well: Jeremy Glick on American Airlines flight 93 with his two month old son, called his wife and told her they had been hijacked, but he also reported that the passengers had voted to attack the terrorists. It would appear that this decision of the passengers and crew aboard the doomed flight resulted in the crash of the plane in a forest instead of into a target like the White House. As the father of several small (and a few not so small) children, the tale that touched me most was of a man on the 80th floor of one of the World Trade Center buildings; he called his wife to say he didn’t think he was going to make it out, he loved her, and to take care of their two small children, ages, one and three.

Nine days ago, at our Selichot services, we watched the movie “The Straight Story.” Based on the story of Al Straight, the movie tells the tale of an elderly gentleman who learns his brother, who he hasn’t talked to in ten years, has had a stroke. Having medical problems himself which have resulted in the loss of his driver’s license, Al hopes on a riding lawnmower for an incredible 360 mile journey of teshuva, of reconciliation.

All too often we wait until a disaster strikes to do teshuva, to return.

The ten days between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur are a period for heightened examination of our lives, a time to make amends; we have the image of decree that will be sealed on Yom Kippur, and closed at the end of Sukkot. The recent events remind us of how real the closure of the book can be, and how sudden.

What would you do, trapped on that plane or in that building? Who would you call and what would you say? How much regret would you feel at the calls you didn’t have time to make?

Life is too short, and its ending too uncertain, to put things off for another day. Call the parent, or sibling, or child who has become estranged. Go home and hug your child and your spouse. If you are still at war with your ex-spouse, declare a truce, for the sake of your children and your own peace of mind. A few years ago, at this time of year I did teshuva with my ex-wife, and asked for her forgiveness; it was a very powerful and healing experience.

Studies have shown that most of the conversation between a parent and child on a typical day is in the form of criticism and giving orders. “Pick up your toys!” “Why didn’t you pick up your toys?” “Why do I have to ask you a thousand times?” Instead, go home and tell your children how much you love them, how special they are. Talk about the day they were born, and your favorite memories of them. If, God forbid, something happens to either of you today, let their memory of you be of a hug and a smile, loving words instead of harsh ones.

In Pirkei Avot, The Ethics of our Fathers, Rabbi Eliezer advises “repent one day before your death.” The point of his message, so tragically testified to by the events of last week, is that you don’t know when you will die: therefore, you should do teshuva today.

Teshuva can serve to reduce the harshness of the decree both before and after a disaster. For those who take R. Eliezer’s message to heart, and try to live in a state of perpetual teshuva with their loved ones, if tragedy strikes it will not be compounded by a lot of unfinished business and unreconciled feelings. For those of us here, doing teshuva now can bring us closer to our loved ones, closer as a community, and ultimately closer to God. The midrash says that it was the powerfully close community that resulted from the teshuva our ancestors did between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur that made it possible for us to receive the Ten Commandments on Yom Kippur.

The last of the three actions called for by Unetaneh Tokef is Tzedaka. I went with a somewhat liberal translation of tzedaka as deeds of kindness. Tzedaka is more often translated as charity; the same basic word in different forms and contexts can mean justice, righteous, a person who is correct, or a saint. Giving tzedaka is both the correct thing to do, and the righteous thing to do. It is obvious how acts of tzedaka can help remove the severity of the decree; some people may be suffering, but if we give of our time, our selves, or our money, we can work to ease their pain, to remove the severity of the decree. Bringing the perpetrators to justice, tzedek, would also help to ease some of the pain as it would help prevent such tragedies from afflicting others in the future.

However, ultimately, there can be no real “bringing the criminals to justice” in this case. If the person behind all this and all of his followers were caught, tried, and executed, we would still not have real justice. The lives of a handful of terrorists cannot compensate for the loss of thousands of people, for the pain that so many survivors will have to live with for the rest of their lives. There is a story of how the nations of the world will have to do teshuva, and what they will have to pay for what they took from Jerusalem; in place of copper, silver; in place of silver, gold. But in place a Rabbi Akiva there is nothing they can bring; they cannot do real teshuva for the sin of killing Rabbi Akiva.

While tzedaka as justice will help ease the severity of the decree when we see the criminals who did this brought to trial or killed, it is probably more important to focus on the tzedaka we can do ourselves: charitable acts.

I was very touched by some of the stories of kindness being shown to strangers in New York. I heard that shoe stores were giving away free sneakers to women wearing high heels who had long walks home because of the shutdown of public transportation. That’s not the kind of thoughtfulness that immediately comes to mind when we think of tough New Yorkers. But I think New Yorkers are like Israelis: they both have a tough, macho exterior, but underneath they have hearts of gold.

Tzedaka is one thing we can all do in a way that can make a real difference to others. We can give money, especially to organizations that help the victims of terrorism. The Jewish Federation of Southern Arizona has set up a special fund to support the victims of terrorism here in the US and in Israel. Information can be found . . . .

We can also give of ourselves; we can give blood, we can volunteer our time. We can talk to others and convince them to give.

We will continue to struggle with our feelings, our fears, our stress in the wake of this incredible tragedy for quite some time to come. If we can remember the prescription of Unetanah Tokef—that “Teshuva, tefila, and tzedeka–repentance, prayer, and deeds of kindness–can remove the severity of the decree”—perhaps we can find the path to healing our own psychic wounds while working to heal the all too physical wounds of thousands of fellow Americans, and hundreds of fellow Jews in Israel.

May the New Year bring us a just and lasting peace in the Middle East, and an end to terrorism everywhere in the world. May Isaiah’s prophecy be fulfilled: Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall mankind learn war anymore.