Noah and Unity

Unity is one of those “motherhood and apple pie” values that everyone automatically assumes is a good thing. America’s formal name is The United States of America; the great international body of nations is the United Nations. And of course we are all familiar with the quote from Abraham Lincoln’s speech before the US Civil War, “United we stand, divided we fall.” In the aftermath of 9/11, “United We Stand” was a slogan plastered all over the States, from bumperstickers to billboards. Ariel Sharon struggled to put together a “Unity government” in Israel, that included representatives from all sides of the political spectrum.

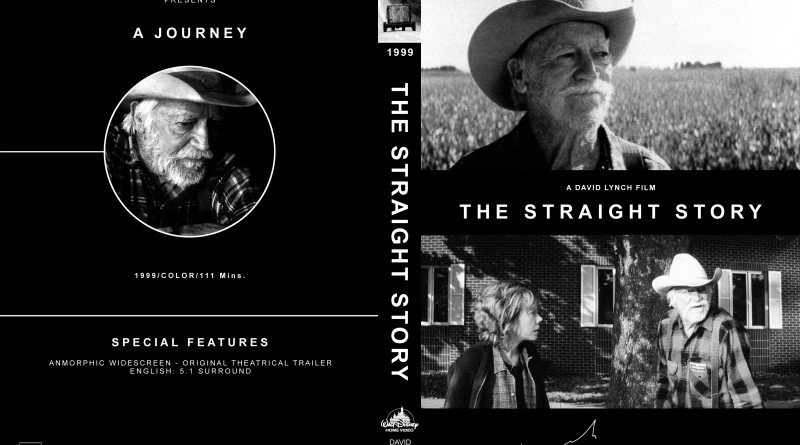

The strength of unity was vividly shown in the movie The Straight Story. There is a scene in the movie when Al Straight is sitting around a campfire with a runaway teenage girl, and he demonstrates that while it is easy to break a single stick, it is very difficult to break a unified bundle of sticks.

In this week’s Torah portion we also have an example of the power of unity. We have the story of the Tower of Bavel, or “Tower of Babble.”

Even though we are all familiar with the basic story, I’d like to read the story to remind us of the details. I’m using the JPS translation:

Everyone on earth had the same language and the same words. And as they migrated from the east, they came upon a valley in the land of Shinar and settled there. They said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks and burn them hard.” Brick served them as stone, and bitumen served them as mortar. And they said, “Come, let us build us a city, and a tower with its top in the sky, to make a name for ourselves; else we shall be scattered all over the world.” The Lord came down to look at the city and tower that man had built, and the Lord said, “If as one people with one language for all, this is how they have begun to act, then nothing that they may propose to do will be out of their reach. Let us, then, go down and confound their speech there, so that they shall not understand one another’s speech.” Thus the Lord scattered them from there over the face of the whole earth; and they stopped building the city. That is why it was called Babel, because there the Lord confounded the speech of the whole earth; and from there the Lord scattered them over the face of the whole earth.

The midrash universally understands that what the people were doing when they said they were “making a name for ourselves” was idol worship. This is why the behavior merited such a strong condemnation from God. You shouldn’t, God forbid, think it was because God somehow felt threatened by the actions of the people. Naot Deshe, a contemporary Torah commentator, says that at the start of this story we had what sounds like a rare and ideal situation—there was one language throughout the land. The people hated argument and peace was great.

Naot Deshe asks what kind of peace is this that leads to such a serious sin, to idol worship? They were united by a love of a thing, by a will to accomplish a common thing, not love for its own sake. He explains that love that depends on a thing will be nullified, and the thing will be nullified. God confused the languages as a test: to see if despite the problems that go with the “language barrier”, the people would continue to act in unity…they failed the test. They were no longer able to work together without the simplification of a common language. They were better than the generation of the flood—at least they weren’t “chamas,” violent; but still their peace was not a real peace. You shouldn’t think that God rewarded their peace with argument, but rather He tested them to see if their peace was genuine.

The Chasidic Silonomer rebbe observed that unity tremendously increases your strength, whether for good or for bad. In our scene from The Straight Story, the bundle is stronger than the individual stick, and this would be true regardless of whether the bundle is being used to save a life or to kill someone.

I would like to suggest a novel interpretation to the reason God chose to disrupt the unity at Bavel: it was not punishment, and it was not a test. Rather, I believe that it was God’s way of solving the problem.

What exactly was the problem? The people were united, but they were united to an evil end. They needed a dissonant voice, they needed a dissenting opinion. They needed a conscience. When God said “If as one people with one language for all, this is how they have begun to act,” I would suggest that God was bothered more by the fact that they were going down an evil path than by the fact that they were strong. It could be that when they quit thinking and speaking with one voice, someone was able to speak up, and say “hey guys, what you’re trying to do is WRONG!—it’s avodah zara, it’s idol worship—don’t do it!” They were scattered—or perhaps they scattered themselves. Is this such a bad thing? If they stayed in one place could they have been vulnerable to another despot who might come and unify them for his own negative ends?

The Jewish community is very united in their support of Israel. We are slightly less united in our views on what would be the best course of action for Israel to take regarding finding a way to end the current violence.

There are those in our community who would say that in the name of unity, we must not criticize Israel at this time. That anyone who criticizes Israel at this time of trouble is somehow a traitor. Jews have been excoriated for being willing to meet with Palestinians, or for being willing to hear their point of view.

Even rabbis, who I would hope would have developed a keen appreciation for dissenting points of view after years of studying Talmud are not immune from this tendency to squelch criticism in the name of “unity.” I would be embarrassed to repeat some of the adjectives that some of my colleagues have used to describe rabbis who participate in the group Rabbis for Human Rights, a group concerned with, among other things, Israeli government maltreatment of Arabs, Bedouins, and other minorities in Israel.

This intolerant attitude toward dissenting opinions is wrong. We need to have dissenting voices to help prevent us from deluding ourselves into building a Tower of Babel. For example, I personally disagree very strongly with Rabbi Michael Lerner, the editor of Tikkun magazine. I often find his views regarding the intents of the Palestinians to be somewhat naïve. However, I fully defend his right to voice those opinions, without censure or condemnation from others in the Jewish community.

If we were to label all dissenting voices traitors, we would also have to label Isaiah, Jeremiah, and most of the rest of our prophets as traitors. I hadn’t thought of the connection between the two stories in this week’s parsha, the story of Noah and the story of the Tower of Babel, until after seeing Daniel’s take on Noah: that Noah was one of those dissenting voices, Noah was one of those people resistant to peer pressure. Noah was a person who did not follow the crowd off the cliff. Noah listened to God, and his internal moral compass, rather than to everyone around him.

Recognizing the wrongs and being critical when the Israeli government does something wrong does not make one a traitor. Sometimes people equate criticizing Israel with supporting or condoning the actions of the Palestinians. Nothing could be further from the truth. Critics of particular policies or particular incidents that occur are motivated not by hate of Israel or love of Palestinians—whether you agree with what they say, or not, they are motivated by a desire to Israel do the right thing, by a desire to see Israel live up to principles of Judaism.

A “loyal opposition” is a good thing. We need dissenting voices. We need to be reminded that there may be unfortunate consequences to whatever course of action we choose to take. When we make decisions, they need to be informed by the best wisdom of not just people who agree with us, but of people who have different perspectives than our own.

When God confused the languages at Babel, he was saying we needed some additional voices. Overwhelming unity can be a very dangerous thing—you can have a society that marches off a cliff, or acts inhumanely because no one was willing to speak up, to be a lone voice in a crowd that does not want to hear dissenting opinions. It can lead to building a tower to idol worship.

I worry whether the unity the Western world shows for the war on terrorism is a true unity, or whether it’s what Naot Deshe called unity for a thing. If the only thing that unites us is a desire to rid the world of Osama bin Laden, we are not really united, and we may have serious problems in the future.

Let us make sure that we are united for the right causes, and that even when we are united we have “many voices,” we are willing to listen to and to respect minority opinions. And may we apply this principle not only in Ottawa and Washington DC, but in our own lives and communities as well.