Lech Lecha 5778 – Jewish Continuity Advice from Abraham

What is it that makes Abraham so special that God singles him out to become the first Jew?

When God spoke to Noah about the coming flood, we’re first told that Noah was a “righteous and pure” man in his generation. That explains why Noah was chosen of that corrupt generation to be the one who is saved, the one who’s the vehicle for saving a breeding couple of every species.

By the time God gets around to talking to Moses for the first time, we know a lot about Moses’ character, especially from the incident when he kills a slavemaster who was beating a Jewish laborer. Clearly he had the right kind of stuff to save the Jewish people.

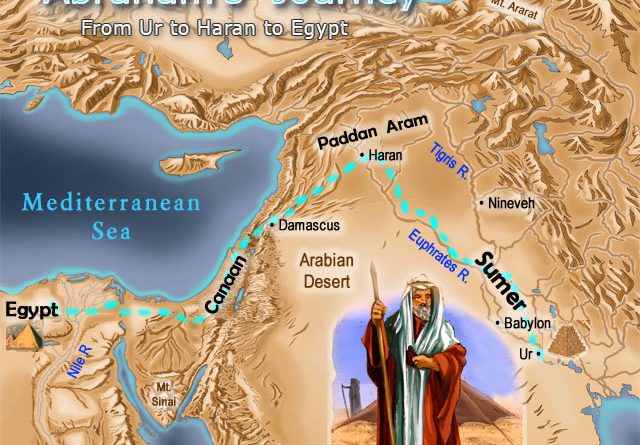

But with Abraham, we know nothing about him, other than his father is Terach, before the opening line from this week’s parsha: “Lech lecha, go forth from your land, from your birthplace, from your father’s house, to the land that I will show you.”

The Hebrew phrase, lech lecha, is unusual: literally, it would mean “go to you,” or “go to yourself.” Many rabbis therefore interpret this verse as meaning it’s talking about a spiritual journey, not a physical journey. Go to yourself, your inner self, your true self. Leave where you are now, and go on a spiritual journey to find yourself and to find God.

The Sfat Emet, a 19th century Chasidic rabbi, said that the message of lech lecha, go out on a spiritual journey to find yourself and God, is one that God transmits to everyone in the world, every day. Abraham was the first one to pay attention, to hear God calling, to choose to go out on that journey.

A few verses later the Torah tells us that Abraham, his wife, and his nephew all headed out on the journey, along with all the wealth they amassed, and hanefesh asher asu b’charan, the souls that they had made in Haran. Which sounds as odd in Hebrew as it does in English; what’s that mean, “the souls that they made in Haran?”

Having heard God calling, Abraham shared that news with other people – and once it was pointed out to them that God was calling on them to go on a spiritual journey, they were able to hear the call as well. And Abraham and Sarah converted them to Judaism, and they joined Abraham and Sarah on the spiritual and physical journey to the promised land.

This is kind of remarkable if you think about it – the very first thing Abraham did after hearing God call, before he even headed out on the road on his own physical and spiritual journey, was to share that message with others, and welcome converts to join him – the first convert to Judaism – on his journey.

Abraham seems to have been very eager to bring converts tachat kanfei hashechinah, under the wings of the Divine presence. So what happened? Why aren’t we out there proselytizing, seeking new converts, the way that Abraham did? And the way many other religions do? Why don’t we have Hashem’s Witnesses out knocking on doors? Missionaries sent off to darkest Africa, as in the Broadway who, The Book of Mormon?

From the days of the revolt of the Maccabees in the 2nd century BCE through the time of the destruction of the Temple in the year 70 Judaism WAS a proselytizing religion. We did actively seek converts – this is attested to by both Josephus, the most famous Jewish historian of that time frame, and Roman authors as well. A number of Roman nobles are recorded as having converted to Judaism. I can’t vouch for its accuracy, but I heard one estimate that said at the peak 10% of the population of the Roman Empire was Jewish. At one time, during the Maccabee era, we even converted people (notably the Idumeans) at swordpoint.

What happened?

After the destruction of the Temple, one can imagine many people would have felt that the Jews had fallen out of favor with their God. A few centuries later, as Christianity began its rise, Jews were a persecuted people. For many years, it was against the law for people to convert to Judaism. Rabbis that converted people were risking severe punishment. It was during this period of time that Jews not only stopped seeking converts, they started to actively reject people interested in conversion. This is the source of a custom still followed in much of the Orthodox world for a rabbi to reject a convert three times before accepting him or her for study. The purpose of that was to make sure the prospective convert was sincere, and not a spy from the secular authorities trying to infiltrate the Jewish people, or trying to catch a rabbi in a “sting” operation.

For many centuries, Jews didn’t exactly welcome converts, but the people who were born Jews, who were born into the covenant, stayed Jews.

“Born into the covenant” – the covenant that God made with the Jewish people is also found in this week’s Torah portion.

I will maintain My covenant between Me and you, and your offspring to come, as an everlasting covenant throughout the ages, to be God to you and to your offspring to come…Such shall be the covenant between Me and you and your offspring to follow which you shall keep: every male among you shall be circumcised…Thus shall My covenant be marked in your flesh as an everlasting pact.

Circumcision is just a sign of the covenant, it’s not the covenant itself. The covenant – the deal – is that we’ll follow God’s rules, and God will be our God. And God throws in giving us the land of Israel as a sweetener to the deal.

Assimilation wasn’t an option for our ancestors who lived in ghettos in Europe. Antisemitism was a very effective way of keeping the Jewish community intact. We lived in our ghetto and kept to our own.

That all started to change with the haskala, the “Jewish Enlightenment,” which started in Germany in the late 1700s when the German rabbi Moses Mendelssohn found that Jews could be accepted and integrated into German society – but an important starting point was they had to learn to speak proper German, not Yiddish. He translated the Torah into German and started giving sermons in German to encourage his community to learn German. The emancipation of the Jews – the granting of full civil rights to the Jews – first by France in 1791, and spreading to other countries in the 1800s – opened new doors for the Jews. There was still plenty of antisemitism however; so many Jews opted for the easy path out, and converted to Christianity. Moses Mendelssohn’s own grandson, the compose Felix Mendelssohn, took that path – which explains why we never play Mendelssohn’s Wedding March at a Jewish wedding.

While assimilation has been around as an issue for a long time, it’s becoming a bigger and bigger issue. The 2013 Pew survey was a real wakeup call to the Jewish community. Prior to 1970, the intermarriage rate among Jews was 17%; today, among non-Orthodox Jews, it’s 71%.

Intermarriage by itself doesn’t have to be a problem for Jewish continuity; we have many intermarried families in our community that are proudly raising their children as Jews; I’m a product of an intermarried family.

The big issue isn’t so much intermarriage as it is Jews giving up on their religion.

Many Jews who were “born into the covenant” consider themselves “Jews with no religion.” This is a growing phenomenon. 19% of the Jews of my generation consider themselves to have no religion; among millennials, my kids’ generation, those born after 1980, the number is 32% who consider themselves “Jews with no religion.”

What the heck does that mean? You’ll never hear a Gentile claim to be a “Christian with no religion.”

It means they were born into a Jewish family, being Jewish is part of their identity, but they aren’t at all “religious.” They don’t see themselves as having a religion.

Intermarried Jews who identify their religion as Jewish still raise their children as Jews 2/3 of the time.

On the other hand, Jews who claim to have no religion raise their children with no religion 2/3 of the time. And those children raised with no religion will certainly no longer identify themselves as Jewish at all. Clearly religious identity is a much more important issue than intermarriage.

And this is the real demographic challenge facing the Jewish people. We stopped actively seeking converts a very long time ago; which was OK when being born into the covenant was sufficient to ensure Jewish continuity. But nowadays, with high assimilation rates, unless we bring as many people in the front door as go out the back door our already small numbers will continue to diminish.

Converts are sometimes called “Jews by choice,” but the truth is we’re all Jews by choice. The ghetto walls are long gone. People freely explore all kinds of different religious beliefs, and the fastest growing religion is “none.” This is a challenge, by the way, not just for Jews – our Christian neighbors face the same issue in their communities.

Why would someone – born Jewish or not – choose Judaism?

Judaism has a great product, but our packaging needs some updating.

What do I mean by that?

For over 2,000 years, the greatest minds in the Jewish world have wrestled with the deepest questions – God, the meaning of life, how to be a good person. We have a path for connecting with God. We have created strong communities. Much of our religion is based in the home and family. We have beautiful rituals that add meaning to the sacred moments in our lives. That’s our product.

Our packaging is the way we present our accumulated wisdom – our services, classes, opportunities to connect with God and each other.

Temple Beth-El is doing the right things. We hired Sarah Metzger in a conscious effort to bring more music to our services and our community. We continue to financially support our religious school and youth groups even with diminished numbers. We offer innovative programs to engage our community.

There are three things we need to do to ensure Jewish continuity, and all three are things we learn from Avraham Avinu, our ancestor Abraham.

The first is honoring the covenant that Abraham made with God. Today we celebrate a bar mitzvah. David is making a statement today – that not only was he born into the covenant, but he has chosen to be a part of that covenant. He is a “Jewish Jew,” not a Jew with no religion. We need to continue to encourage our children to make that choice by providing them with a solid Jewish education, positive Jewish experiences such as Jewish summer camps and youth groups.

The second is following the example of Abraham at the start of his journey – we need to invite others to join us. We have much to offer a world where people are increasingly more connected to their devices than to each other, a world where people can go to a beautiful place in nature and be looking at their phones instead of appreciating the awe and wonder of being surrounded by God’s awesome creations. We don’t necessarily need to go around knocking on doors like Jehovah’s Witnesses, but we should be out there competing in the marketplace of religions, and let those who may be interested know what we have to offer.

And the third thing we need to do that we learn from Abraham is something we learn in next week’s parsha, Vayera: being welcoming. From Abraham’s example of welcoming three strangers into his tent and feeding them we learn the mitzvah of hachnasat orchim, welcoming visitors. Being a welcoming community is vitally important, whether it’s inreach – reaching out to fellow Jews – or outreach, reaching out to the broader community. Our Keruv program is exactly the right thing to be doing. We need to strengthen those efforts; every member of Temple Beth-El should view him or herself as an ambassador for our community, as part of the “welcoming committee.”

The surveys on Jewish demographics are dire. Many commentators look at the surveys and say, “If present trends continue, the only Jews left in America will be Orthodox.”

We don’t have to let present trends continue.

May the Kadosh Baruch Hu, the Holy One, blessed be He, strengthen us in our efforts to keep the light of Judaism shining brightly for many generations to come,

Amen