Naso 5778 – Offering Blessings

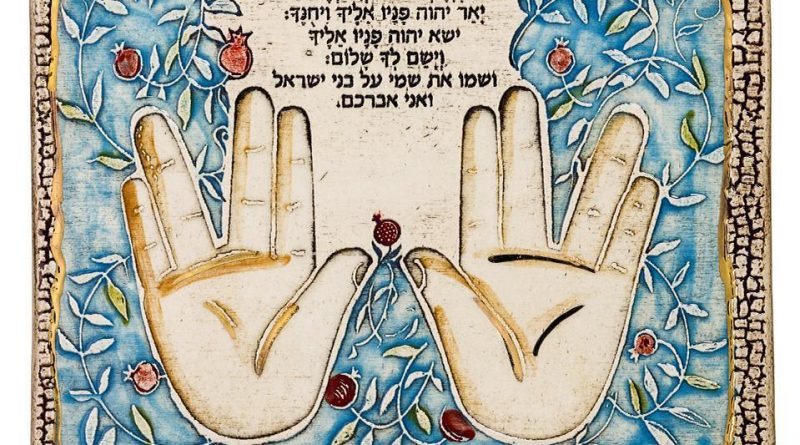

And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, Speak to Aaron and to his sons, saying, thus shall you bless the people of Israel, saying to them, May the Lord bless you, and keep you; May the Lord make his face shine upon you, and be gracious to you; May the Lord lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace. And they shall put my name upon the people of Israel; and I will bless them.

Number 6: 22-27

Mallie spoke wonderfully about how special it is that her parents bless her with the same blessing that has been used for generations, l’dor v’dor, the same blessing that God commands the Kohanim, the priests, descendants of Aaron, to use to bless the people.

In Israel it’s the custom in most synagogues, including many Conservative synagogues, for the Kohanim to bless the congregation with this blessing not only on festivals, but every Shabbat. This custom has fallen out favor in America; in our synagogue, as in many others, the Kohanim never give this blessing to the congregation. It seems somehow against our egalitarian ideals to think there’s a role reserved for certain people only by virtue of lineage.

I think that’s a pity. If I were here permanently, I’d work with the ritual committee to see if it made sense to bring that priestly blessing back. It’s always a spiritual moment for me in shul on Shabbat in Israel when my friends who are Kohanim go to the bimah and bless us with those same words…

Y’verekhakha Hashem v’yishmerekha May God bless you and keep you

Ya’air Hashem panav alekha vikhunekha, May God raise His face to you, and be gracious to you

Yisa Hashem panav alekha, v’yasam l’cha shalom, May God raise his

countenance to you, and grant you peace

The non-egalitarian nature of the ceremony doesn’t bother me at all. Our genetics determine a lot of things about us. There are certain things only men can do and certain things only women can do. Some people are blessed with genes to run a marathon in under 3 hours. I’m not one of them. When I was 20 I could have trained as hard as physically possible, yet I never would have achieved that goal.

I feel a palpable connection with the past when the Kohanim, direct male descendants of the first high priest Aaron, channel for God when they give the congregation that blessing. As much as I enjoy that feeling of historical connection, the truth is you don’t need to be a kohen to bless someone. As Mallie shared, parents, and not just Kohanim, bless their children with this blessing every Friday night. When I’m not with my kids, I give them their “Shabbos blessing” using FaceTime, where ever in the world I or they are. Yesterday I blessed one daughter in Uganda and two daughters in Israel.

Anyone can bless anyone else, as is illustrated by a couple of beautiful stories in the Talmud: In tractate Brachot we have a story of R. Ishmael b. Elisha who says:

I once entered into the innermost part [of the Sanctuary] to offer incense and saw Akathriel Jah, the Lord of Hosts, seated upon a high and exalted throne. He said to me: Ishmael, My son, bless Me!—I find this remarkable: God asks a mortal for a blessing!–R. Ishmael replied: May it be Your will that Your mercy may suppress Your anger and Your mercy may prevail over Your other attributes, so that You may deal with Your children according to the attribute of mercy and may, on their behalf, stop short of the limit of strict justice! And God nodded to me with His head. From this we learn that the blessing of an ordinary man must not be considered lightly in your eyes. The gap between R. Ishmael and God is surely greater than the gap between any two people…yet God still appreciated his blessing.

In fact to be denied a blessing, is clearly seen as a deprivation. Look at the struggle between Jacob and Esau when Jacob intercepts a blessing intended for Esau through deception. Esau’s cry to Isaac, “don’t you have another blessing for me!?” is one that the rejected child in all us of can relate to.

The Talmud gives us another example of how a blessing even from someone of lower status than one’s self is to be cherished. In the Talmud tractate Chagigah we get the following story:

Rabbi and R. Hiyya were once going on a journey. When they came to a certain town, they said: If there is a rabbinical scholar here, we’ll go and pay him our respect. They were told: There is a rabbinical scholar here and he is blind. Said R. Hiyya to Rabbi: Stay [here]; you must not lower your princely dignity—Rabbi was the Nasi, the head of the Supreme Court, and R. Hiyya thought it would somehow be undignified for Rabbi to go visit this blind scholar. R. Hiyya said, “I shall go and visit him.” But [Rabbi] took hold of him and went with him. When they were taking leave from the blind scholar, he said to them: ‘You have visited one who is seen but does not see; may the one who sees but is not seen visit you.’ Rabbi said to R. Hiyya: If I had listened to you, you would have deprived me of this wonderful blessing.

What does it mean to give a blessing? What power do we people have to bless? The tradition tells us that when we offer a blessing, we are really “channeling” for God. The blessing ultimately comes from God—the person saying the blessing is just a vehicle, drawing God’s presence down for another person. This is alluded to in the continuation in the Torah of the Priestly Blessing. After God tells Moses the formula of the blessing He continues “And they shall put my name upon the people of Israel; and I will bless them.” Which makes clear that ultimately it is God doing the blessing. For this reason, we don’t need to worry about the qualifications of someone who is blessing us. As you see the Kohanim go up on bimah, you don’t have to worry about whether or not you might be receiving a blessing from someone who is not worthy or suitable to give a blessing. In the Yerushalmi Talmud they bring a teaching which says, “Where do we learn that one should not say “How can John Doe, who is a fornicator and murderer, bless me? God says, “Who is blessing you? Isn’t it I that blesses you, as it says, ‘And I will bless them.’”

Despite all of these examples of the power and importance of blessing others in our tradition, it’s a custom which has sadly fallen into disuse in the Jewish tradition. This was really brought home for me when I had my hospital chaplaincy course in rabbinical school. In the chaplaincy course I made the rounds with a rabbi who is a full-time chaplain at UCLA medical center. He visits both Jewish and Gentile patients. The Jewish patients almost never ask for a blessing, and sometimes they seem a little awkward if we offer a mishebarach, a prayer for healing. On the other hand, the non-Jews we visited would frequently say, “say a prayer for me.” I was very impressed watching Rabbi Winnick make up a blessing on the spot, one that used traditional elements so it was clearly a Jewish form of blessing, but one that also dealt with the specific situation of the person he was talking to. The recipient inevitably was very appreciative.

Maybe we’ve gotten out of the custom of offering spontaneous blessings to each other because we’ve gotten too used to relying on the siddur for all of our spiritual needs. Spontaneous blessings and prayers are not part of the daily synagogue ritual.

The most beautiful spontaneous blessing I’ve ever received was from my kids. On Friday night at the Shabbat table, we always bless our kids. One week then 7-year-old Katherine said, “you should have a blessing too,” and she got up, put a hand on my head, and said, “baruch ata hashem, elokeinu melekh haolam (Blessed are you, Lord our God, ruler of the universe), I love Abba.” What a fantastic blessing!

Which shows that blessings don’t need to be long, or complicated, or written in the siddur to be meaningful.

One of the things I appreciate about my friends who are Jewish Renewal rabbis is that every so often when we’re parting, or if I just seem in need of a blessing, they’ll give me a blessing. It’s really a nice thing. I’ve learned to try and reciprocate and offer blessings as well.

I encourage you to give it a try. Give someone a blessing today—whether it’s a loved one, a friend, or a stranger who looks like they could use a blessing in their lives. You can offer your blessing in any kind of format that works for you—using some traditional language, or completely in contemporary English, whatever feels comfortable for you. It may seem a small thing, but saying “May God (or the Holy One, or the Compassionate One, or …) grant you…” instead of “I hope” gives your good wishes a lot more power.

May we all bring more blessings into our lives.

Shabbat Shalom!