Colleyville, Anti-Semitism, and Being True to Who We Are

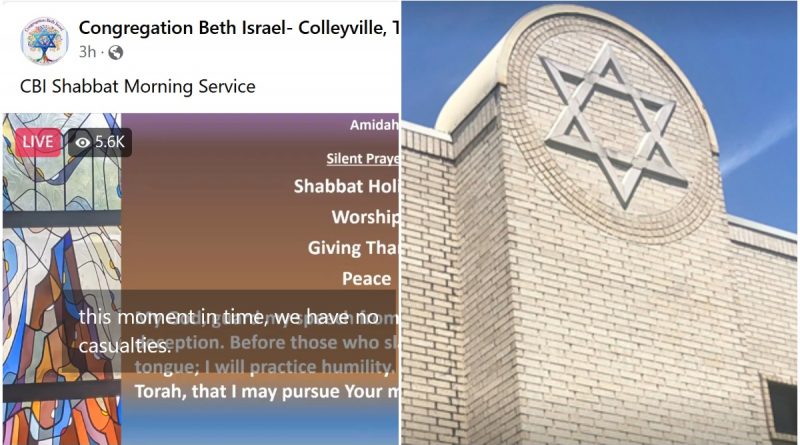

We were all shocked by what happened in Colleyville, Texas, last Shabbat.

A rabbi and three other people who were celebrating Shabbat morning services were taken hostage by an anti-Semitic British Muslim who was hoping to secure the release of an accused terrorist sitting in an American jail. The initial stages of the situation were seen on the synagogue’s Zoom broadcast of the service.

The Jewish world is such a tight-knit community that we all felt, “that could have been me.”

For rabbis, that feeling was especially strong. It’s a pretty good bet that almost every non-Orthodox rabbi in America knows someone who knows Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker. Several of my rabbi friends know him personally. That really ramps up the feeling of, “it could have been me.”

Thanks to the security training the rabbi went through, along with his patience and decisive action at the right moment, the hostages managed to escape, and the kidnapper was stopped by law enforcement.

As shocking as the attack itself was, the Jewish community was disheartened when the FBI Special Agent in charge of the Dallas office said,

We do believe from our engagement with this subject that he was singularly focused on one issue, and it was not specifically related to the Jewish community. But we are continuing to work to find [the] motive.

In other words, he felt that since the attacker’s goal was securing the release of someone, and not focused on simply terrorizing Jews, it wasn’t an anti-Semitic attack.

Which of course, is absurd. Why would this man choose to attack a synagogue to accomplish his goal if it wasn’t for anti-Semitism? Why didn’t he take over a church and make the same demand?

One of the hostages, Jeffrey Cohen, explained how we know it was anti-Semitic:

He terrorized us because he believed these anti-Semitic tropes that the Jews control everything, and if I go to the Jews, they can pull the strings. He even said at one point that ‘I’m coming to you because I know President Biden will do things for the Jews.’

He called the person he was trying free – Aafia Siddiqui – his sister. She was not his biological sister, she was his spiritual sister. Siddiqui was shooting at US Army troops as they arrested her. But she claimed the case against her was a “Jewish conspiracy,” and she dismissed her legal team because she said the lawyers were Jewish. She then tried demanding that jurors at her trial take DNA tests. She wanted to make sure none of the jurors were Israeli or Zionists, in order “to be fair.” For a woman who has a PhD in neuroscience – from Brandeis University, no less, a heavily Jewish institution – it’s pretty ignorant to think “Zionism” shows up in your DNA. Some of the most ardent Zionists are evangelical Christians.

After public outcry the FBI walked back their statement about the attack not being specifically related to the Jewish community. A later statement said, “This is a terrorism-related matter, in which the Jewish community was targeted.” The FBI also said it will “never lose sight of the threat extremists pose to the Jewish community and to other religious, racial, and ethnic groups.”

Anti-Semitism nowadays takes many different forms – there’s the anti-Semitism of the white nationalists, the anti-Semitism of Muslim extremists, the anti-Semitism masking itself as anti-Zionism on the left.

What these different forms of anti-Semitism all have in common is they are based on dislike of Jews because we’re different. We stubbornly cling to our beliefs and traditions, we don’t accept Jesus or Mohamed or campus cancel culture.

And it’s infuriating when some people use anti-Semitism as a cover to advance their own political agenda which is contrary to the views of most Jews. Republican Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri wrote a public letter where he said:

I write with alarm over reports that the Islamic terrorist who took hostages at a Jewish synagogue in Texas this past weekend was granted a travel visa. This failure comes in the wake of the Biden Administration’s botched withdrawal from Afghanistan and failure to vet the tens of thousands who were evacuated to our country.

Reading that we’re left shaking our heads and going “huh?” The attacker didn’t come from Afghanistan – he came from the United Kingdom. He wasn’t a refugee. And Jews are some of the strongest supporters of refugees in America, because we know what it’s like to be fleeing for your life only to have trouble finding a country that would take you.

That spirit of being welcoming was present in Colleyville. The rabbi let the attacker in and made him a cup of tea.

Do we need to stop being so welcoming?

I think that would be a mistake, and I’ll explain why.

Scary attacks such as this one, or the shootings in Pittsburgh and Poway, are scary, but they are very rare.

There are an estimated 4,000 synagogues in the United States. Assuming each had services every Shabbat, that’s 208,000 Shabbat worship services in a year. That one experienced a hostage taking is terrible, but one out of 208,000 is a minuscule number. Your chances of being killed in a car accident any given year are far far higher – one out of 7,132 in 2020.

And I suggest that’s the way we need to look at synagogue security – similar to the way we view car accidents.

We do what we can to prevent them, and to minimize harm in case an accident happens. We maintain our cars, we wear our seatbelts, we make sure drivers are properly trained, but we accept that there is a level of risk we are comfortable with. We don’t quit driving and we don’t insist on driving only armored vehicles.

Similarly, we should take reasonable security precautions – as we do here at Temple Beth El. Rabbi Cytron-Walker reported how important the training he received was in their escape, so it would be a good idea for a few members of our community to have some training. If it makes you feel better knowing I’m around, I have a black belt in Tae Kwon Do, and can throw a chair with the best of them, but I’d be happy to get additional training.

But it’s important that we remain true to who we are. The Torah charges us with being kind to the stranger, and we should not stop doing that.

In an interview after he was released, Rabbi Cytron-Walker said, “We have to be hospitable and we have to be secure. And we have to find ways to strike that balance.”

Even after what he went through, Rabbi Cytron-Walker said we cannot cease to welcome the stranger. He said,

I’ve welcomed people into the congregation that don’t look like your stereotypical visitor to a Jewish synagogue, over and over and over again. And people are looking to pray. People are looking for community. And they’re asking the question, ‘Do I belong?’ And we need to stress to them, and the whole community has to be able to stress to them, that yes — you belong.

Every rabbi has stories like that. Especially when I was serving a congregation in Birmingham, Alabama I had a lot of visitors who didn’t look like the stereotypical visitor to a Jewish house of worship, but my doors were open, and I listened, and helped who I could.

We should do what we can to be secure, but at the same time, we can’t make security the only thing that matters. We have to be true to our Jewish values and remain a house of prayer open to all, welcoming the stranger, just as our father Abraham welcomed strangers into his tent.

Shabbat Shalom