Yom Kippur 5783 – Bill 96 and Jewish Identity

I came to Montreal in May to look for a place to live. Pretty much everyone from the community with whom I had a conversation that lasted more than five minutes brought up Bill 96. And how bad it was for the Anglophone community in Montreal.

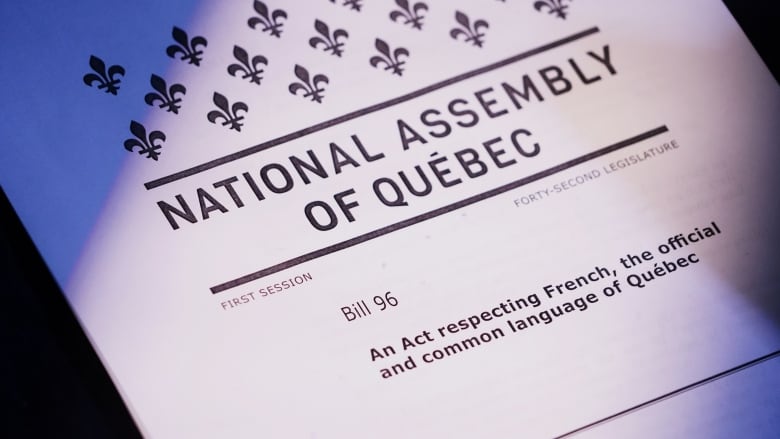

As you know, I’m not from Quebec. I don’t know one political party from another, and I don’t know all the bills that preceded “An Act Respecting French, the Official and Common Language of Quebec.” I wasn’t here during the heyday of the Quebec separatist movement.

So I have an outsider’s perspective. From everything I’ve heard, the bill increases a feeling of disrespect among the English-speaking community, and it’s probably going to make the province less competitive in attracting multinational corporations, as they generally operate in English. With a mandate that even temporary workers have to send their children to school in French, it will make it more difficult for the congregation to hire a rabbi with school age kids who is coming from the States.

It’s quite possible that the bill, and previous bills like it, were passed because of the increase, not just in Quebec, of “identity politics,” where nationalists use identity-based issues to drive division and pick up voters from a large group that feels, nonetheless, under attack, as Donald Trump did in the US with white nationalists.

But a question I wanted to ask was, “Why?” What’s driving these bills and this drive to make French not just a preferred language but practically the only language in the province?

I believe the answer is fear. And in particular it’s fear of assimilation.

There are eight million Francophones in Canada, surrounded by 360 million English speakers in North America. They make up approximately 2% of the population of North America.

The Francophone community has good reason to be concerned. Statistics Canada reports that the percentage of Canadians who speak French at home continues to decline, even in Quebec.

Federal Minister of Official Languages Ginette Petitpas Taylor responded to the new data saying,

The census data on official languages released this morning is troubling, and demonstrates what our government has always said: French is under threat in Quebec, as it is across the rest of Canada. For the eight million francophones in Canada who exist in an ocean of more than 360 million English speakers across North America, we know that we must be vigilant in protecting and promoting French, and that is why our government has made it a priority.

There are a lot of different reasons for the decline. The fertility rate in Quebec is low, only 1.5. That means the local born, majority French population is shrinking.

With an otherwise shrinking population, Quebec needs immigrants to fill jobs and support the economy, but most immigrants don’t speak French. Their native language is likely neither English nor French, but English is seen as the generally preferable language to learn, because it is useful in so many different places.

For many generations, French Canadians provided a lot of unskilled labor in Quebec, while the ruling elite spoke English. This has encouraged many native French speakers to learn English in order to advance socially and financially. Until recently, the reverse has not been true.

The Quebecois fears around assimilation are fears that the Jewish community should be able to readily identify with. As many headlines that antisemitism gets, assimilation is actually a much greater threat to the continuity of the Jewish people. Many Orthodox rabbis even call assimilation a “Silent Holocaust.”

The situation of Jews in North America is in some ways similar to the situation of Francophones. Jews and Francophones each make up around 2% of the population in North America. A drop in the bucket.

For Jews, in many ways, the situation is more difficult. We are not highly concentrated in one area, as are the French speakers in Canada. We speak the local language of wherever we live, most Jews don’t even speak Hebrew as a second language. Very few Jews go to college on a campus where Jews are a majority. As a result, intermarriage rates are over 50%, meaning two out of every three weddings involving a Jew is an intermarriage.

The Jewish community historically responded to the threat of assimilation in much the same way the Francophone community in Quebec is responding: with a “circle the wagons” mentality.

In the 1800s when wagon trains made their way across America, in times of danger they would gather the wagons together in a circle, close together, to form a defensive barrier against any dangers that would be kept on the outside.

We can see signs that the Jewish community adopted a similar “circle the wagons” mentality nearly 2,000 years ago, after the destruction of the Temple.

After the Temple was destroyed, the bulk of the Jewish community was split into two locations, Bavel, or Babylonia, and Israel. There were academies for Torah study in both places, which is why we have two versions of the Talmud, the Bavli and the Yerushalmi, the Jerusalem or Palestinian Talmud.

Even though the Babylonian community was the stronger of the two, they were living in galut, in exile. They were no longer in our ancestral home, in Israel. The community developed a “circle the wagons” mentality, and the way they mounted their defense was by taking a stricter approach on matters of Jewish law and being more stringent in separating from the non-Jewish community around them.

There is a passage in the Yerushalmi that criticizes taking on unnecessary stringencies. It says one who is exempt from doing something and does it anyway is considered an ignorant person.

That attitude is foreign to the attitude of the rabbis in Babylonia. They took on more and more stringencies.

The Ashkenazi community kept going in the strict tradition of Bavel, while Sefardi Judaism for the most part continued a more relaxed approach in keeping with the spirit of the Yerushalmi.

One example can be found in the different approaches taken to dishwashers. The Shulhan Arukh is still considered today the leading Jewish law code even though it was written 500 years ago. Despite the fact that the Shulhan Arukh says it’s OK to wash meat dishes and dairy dishes together in the same sink, in many Ashkenazi circles they would not use the same dishwasher, even at different times, for both meat and dairy. Some homes have two dishwashers. Whereas Ovadiah Yosef, who served as the Sefardi Chief Rabbi of Israel, ruled that it’s OK to run meat and dairy dishes together at the same time in a dishwasher.

Why the differences? The Enlightenment, the time when Jews became full citizens and were able to freely integrate into society if they so desired arrived much later in the Middle East than it did in Northern Europe. Assimilation was a bigger threat in Northern Europe than it was in North Africa.

There are two different paths to combatting assimilation, the carrot and the stick, encouragement and compulsion.

Bill 96 represents the path of compulsion. Premier Legault also wants to prevent more non-French speaking immigration. He said in a recent speech that allowing more non-French speaking immigration would be “suicidal.” He believes his anti-immigrant stance is justified, because, he said, “No one can deny French is in decline.”

But what’s the price of compulsion?

Blocking immigration will likely have negative financial consequences. With an aging population reproducing below replacement level, it will be hard for the province to fund vital services such as health care and support for the elderly without new workers paying taxes who come from elsewhere.

I’ve had more than one person tell me that their fully bi-lingual children have either left the province or plan to leave the province, not because they can’t speak French, but because they feel unwelcome, and they believe there are better career opportunities available for English speakers in Toronto, Ottawa, or the States. Quebec’s loss will be Ontario’s gain.

The province will have less success in attracting multi-national corporations looking for a base in Canada. Like it or not, English is the international language of commerce, and insisting that employees doing an assignment of a few years’ duration here navigate their lives in French will be a turn-off to many.

English is also the international language for tourism. If important instructions – such as rue barre – are only given in French, tourists may find themselves in dangerous situations that can also inconvenience locals.

The path of compulsion in the Jewish fight against assimilation has similar negative consequences.

Adding unnecessary stringencies as a way to make the walls higher and keep the outside world at bay makes living a Jewish life more difficult and less attractive.

The NYTimes recently ran an expose on haredi schools in New York City that receive millions of dollars in public money, and produce students who can’t speak English (their first language at home is Yiddish), can’t do any math beyond simple arithmetic, don’t know how to use a computer or access the internet, and have no understanding of science. In other words, students who cannot possibly get a real job in the real world. They wish to protect the purity of the community and prevent assimilation by living in a sealed off Yiddish speaking bubble. But that means their community produces no doctors, lawyers, or car mechanics. All it produces are Torah scholars who can do nothing but teach Torah. And as some of the young people escape from that community and its excessive restrictions, they struggle to learn the skills needed to get a job, or to form meaningful relationships outside the confines of arranged marriages.

Once upon a time if a child married someone who wasn’t Jewish, the parents would sever contact with the child, and would actually sit shiva, a symbol that the rebellious child was dead to them.

What a horrible price to pay! To be estranged from your own flesh and blood, simply because of who they fell in love in with.

Guilt is somewhat related to compulsion – it’s part of a “stick” approach. A few years ago, a leading Orthodox rabbi, Efrem Goldberg, was talking to a group of teens about intermarriage. He told them,

It would be easy to argue that we owe it to our grandparents who suffered through the Holocaust and lost so much in the name of Judaism to remain Jewish. But, as Rabbi Korobkin demonstrated so importantly in a recent article, teenagers and millenials are not moved, convinced or inspired by what they perceive as clichéd answers. Anti-Semitism as a motivating factor for Judaism is simply not compelling today and perhaps never was.

In a few minutes we’ll be reciting the Yizkor prayers, when we remember our departed loved ones. And it’s pretty natural that just as we’ll be reciting these solemn prayers for our ancestors, we want to feel like there will be someone to say these prayers for us.

But how do we assure Jewish continuity? How do we pass our pride in being Jewish down to our children and grandchildren?

Many years ago, when I was just starting out in my rabbinic career, serving a congregation in Vancouver, an Israeli who was not a congregant, just someone in the community, made an appointment to see me. “Rabbi, my 25-year-old son is dating is a woman who is not Jewish. I’m quite upset. Having Jewish grandchildren is very important to me. What can I do about it?”

I asked him, “Do you do anything Jewish at home?”

He told me no. “I’m a secular Israeli. I don’t do religious stuff.”

I told him it was too late, there really wasn’t anything he could do about it.

Israel is the only place in the world where you can be a totally secular, disconnected Jew, and still have a pretty good chance of having Jewish grandchildren. That strategy does not work so well in North America, where there are no barriers to Jews assimilating into the dominant non-Jewish culture.

The reason I asked him whether he did anything Jewish at home is because I believe that’s really the key to a strong Jewish identity that can survive for generations. If someone grows up in a Jewish home where Shabbat is the highlight of the week, celebrated with good food, family and friends, where the holidays are marked with joy and gatherings, the children will grow up wanting to have a Jewish home. And if they do fall in love with someone who’s not Jewish, they’ll still want to have a Jewish home.

Kids learn much more from what we do than from what we say. Seeing a parent read Jewish books, hearing discussions of serious topics in a Jewish context, whether it’s words of Torah or something philosophical, means more than sending kids to a Jewish day school and then never engaging with Jewish topics in dinner table conversation.

Positive Jewish experiences are vitally important – Jewish summer camps, Birthright trips, youth groups will do more to encourage a Jewish identity than trying to guilt young people with things such as “do you want to be the one that breaks a link in a 3,000 year long chain?” Or, “your Zeide would be so disappointed.”

And it’s not enough to just go through the motions. A friend was raised in an Orthodox home, and he hated Shabbat growing up. It was all no – no – no. His father sat with his nose in a newspaper all day. He couldn’t wait for the day to be over, and when he went off to college he left Shabbat and any kind of observance behind.

My kids, on the other hand, grew up having fun on Shabbat. They would put on “parsha plays” as the after-dinner entertainment on Friday nights. I was often recruited to play God or Moses. We always had time to play a game, or go to the park. They are much likelier to want to keep Shabbat part of their lives, than the kid who grows up in the home where it’s all no – no – no. And, of course, they each find their own way to mark Shabbat – they don’t necessarily do it the way I do it, and that’s OK.

And even with Shabbat being fun, some kids will assimilate anyway, and that’s OK too. I love all five of my daughters, whether they’re Jewish, pagan, or secular, and whoever they fall in love with or where they live.

Sitting shiva for an intermarried child is a way to guarantee that the interfaith family will NOT create a Jewish home. Intermarriage can be as much an opportunity as it can be a threat. If I hadn’t married a woman who wasn’t Jewish, I never would have become a rabbi. Even though I had a bar mitzvah at 13, I was a completely secular Jew for decades. It was my ex-wife’s interest in Judaism that got me interested in Judaism when I was in my 40s. I’m quite certain when she embarked on a path toward conversion – motivated by her own interest – she had no idea she’d end up married to a rabbi and living in Israel. God works in mysterious ways, indeed!

When we put the Torahs away in a little while, we’ll sing, col darcheha darchei noam, v’col n’tivoteha shalom, “Its [the Torah’s] ways are ways of pleasantness and all of its paths are peace.”

Or as we say in English, “you catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.”

G’mar chatimah tovah