Yitro 5783 – Revelation

How do we know what God wants us to do?

Jews believe it’s based on the Torah, which was given at Mount Sinai. Mount Sinai is a harsh and beautiful place. When I was in Israel at the end of December, I spent a few days in Sinai with two of my daughters and their mother, and one of the things we did was climb to the top of Mount Sinai, starting at the Santa Katarina monastery at the base.

Moses was 80 years old at the time he led our ancestors out of Egypt, and all I can say is he must have been one very fit 80-year-old. The summit of Mount Sinai is at an elevation of 2,400 meters. It’s a 5km hike with 800m of elevation gain, the final section very steep. It December it was quite chilly at the top, and you definitely feel the altitude.

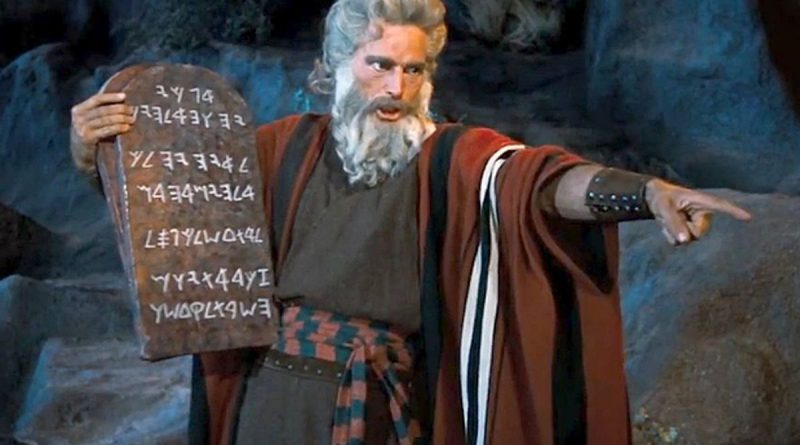

This week’s Torah reading, Yitro, is at the heart of the Jewish understanding of revelation. It contains the Ten Commandments. The Torah says, “there was thunder, and lightning, and a dense cloud upon the mountain, and a very loud blast of the horn; and all the people who were in the camp trembled.”

Moses had warned the people not to “break through” and go up to the mountain. Nonetheless, God tells Moses, “go tell the people not to come up to the mountain.” Moses, says, “yes, I told them.” But God tells him a third time to tell the people not to go up the mountain. Clearly receiving the word of God is supposed to go through an intermediary – through Moses. Not everyone is to hear the words of God directly.

Moses is up on the mountain for 40 days and nights, without eating or drinking. There’s a midrash that says he was on such a high spiritual level at that point that his body was nourished directly by the Shechinah.

The core revelation to Moses, the heart of the Torah, are the words God gave to Moses on the mountain that day – aseret hadibrot, the Ten Commandments, although “ten statements” is a more accurate translation of the phrase. There’s a debate among the rabbis about whether the first commandment, “I am the Lord your God” is a commandment or not. Some see it as a preface, a simple statement of fact. The “whereas” clause.

The Ten Commandments are revered by both Jews and Christians.

A comprehensive survey conducted a few years ago found that 73% of all Canadians – including people who are inclined to reject religion, or who are ambivalent about religion – believe the Ten Commandments still apply today. Not surprisingly, among those who embrace religion, 91% say the Ten Commandments are still relevant.

Yet for all the reverence we give the Ten Commandments, there’s a surprising lack of knowledge about the Ten Commandments. Some years ago, there was a Congressman from Georgia, Lynn Westmoreland, who wanted to pass a bill that would mandate the display of the Ten Commandments in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. After all, the Ten Commandments are a fundamental value we can agree on, right? Westmoreland made an appearance on Stephen Colbert’s program; Colbert asked him, “So what are the Ten Commandments?” A somewhat stricken looking congressman says, “you want me to name them all?” “Yes.” Westmoreland could only come up with three – don’t murder, lie, or steal.

Most people can do a little bit better than three. How many do you remember?

I’ve found most people get to somewhere between six and eight.

Why are the Ten Commandments so popular in the collective consciousness?

One reason is they are the heart of the most famous theophany in the Torah, God talking to Moses. Another is that they seem so simple and straightforward, easy to understand. Theoretically, you COULD memorize all ten if you chose to. The straightforwardness of the ten commandments leads some people to ask “Why can’t we use the Torah, and its clear statements like the ten commandments, to define Judaism and run our lives? Why do we need the Talmud filled with page after page of interpretation? Why do we need all these rabbinic enactments and rules? Why can’t we just follow what’s written in the Torah, and be done with it?”

Let’s take a look at what we have in this week’s parsha, the ten commandments, and see how that would work out.

Let’s examine one of the commandments and see how it works without rabbinic interpretation. How about the 4th commandment, to keep the Sabbath? Can’t we just do what it says in the Torah? Shabbat would be very different without the interpretation of the rabbis. For one thing, we wouldn’t light Shabbat candles: that commandment’s not in the Torah anywhere. In fact, the Karaites, a religion that split off from Judaism in the 8th century, sit in the dark on Shabbat. They don’t believe in the Talmud and rabbinic interpretation: they claim to just strictly follow what’s in the Torah. But isn’t sitting in the dark (and cold, no furnaces going on Shabbat either) an interpretation of some sort? Most of us would probably have trouble saying this is the way God wants us to spend the holy day of rest. I’ll take the Shabbat of the rabbis, with a good meal, good wine, a warm house, and candlelight over the literal interpretation of the Karaite Shabbat any day.

You might say, well, those are religious issues. OK, we need the rabbis to interpret religious issues for us, but the other five of the ten commandments, the ones that are between people, surely, we can follow those without help from the rabbis.

Let’s examine commandment number 9: not to testify falsely against your neighbor. There are those, the philosopher Immanuel Kant among them, who would insist that this is an absolute. You should never, under any circumstances lie. If you were hiding Jews in your basement, and the Nazis knocked on your front door, you should admit you had Jews in the basement.

Most of us would say common sense tells us that you should lie in this situation. That’s what the rabbis did: they applied common sense, and they have a scriptural basis for it. The Torah says these are the commandments and “you shall live by them,” not “die by them,” therefore to save a life overrules other commandments. But we would not have gotten to this application of common sense without rabbinic interpretation. Taken at face value we would be put in the bind of doing some terrible things to obey what it says in the Bible.

Even seemingly simple commandments – do not murder, do not commit adultery – need interpretation. Do we all have to be pacifists, like the Quakers? Or are we allowed to kill someone to defend ourselves? What exactly constitutes adultery anyway? There are all sorts of improper behavior that may or may not be included in that term.

It’s the interpretation of the rabbis that makes the Torah a Jewish text. Other people can look at the same words we read and draw different meanings from them.

Going beyond this interpretive role, much of what we accept as the heart of Judaism are practices that come from the rabbis. There is a long list of blessings where we recite with the formula “Blessed are you Lord our God, ruler of the universe, asher kedishanu b’mitzvotav vitzivanu…who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us to….” that do not appear in the Torah anywhere. The commandments developed by the rabbis, like lighting Shabbat candles, lighting holiday candles, reciting Hallel on holidays are given the same status as other mitzvot; we recite a formula saying that God commanded us to do these things, when in fact these are mitzvot that do not come directly from the Torah. Some may be ancient traditions from the Oral Law which tradition says was also given over at Mt. Sinai; some come from a much later time. We say the bracha that God commanded us to light Chanuka candles, when Chanuka was more than a thousand years after the giving of the Torah.

Those of you who know your Torah might object: doesn’t it say in Deuteronomy (twice, chapters 4 and 13) “do not add to the word which I command you, neither shall you diminish from it?” Aren’t these rabbinic enactments adding – or taking away from – the Torah?

There is a commandment in the Torah to execute a rebellious son by stoning him. The rabbis in the Talmud essentially rendered this commandment inoperative. They put so many limits on it that it became impossible to implement. Isn’t this diminishing from something that’s in the Torah?

Judaism would have died off long ago if it were not for the fact that the rabbis have been able to continue interpreting the Torah, keeping it alive for us. The rabbis’ authority to do this is also derived from the Torah: In Deuteronomy chapter 17 we are told to go to the judge who shall be in those days and inquire, and what they declare the judgment we shall do. We are to go to the judges in THOSE days…in OUR days and inquire, not just go to the Torah, or go to the judges of 15 generations ago.

Through a careful process of interpretation, we seek to understand how to apply the Torah to our lives today. When rabbis today forbid using a computer on Shabbat they are not creating a new mitzvah, rather they are interpreting the commandment we have in this week’s parsha to remember the Sabbath. When the rabbis of 200 years ago said women could not be rabbis, but the rabbis of today say they can, it doesn’t mean the rabbis of 200 years ago were wrong: it means times are different, and the way we apply Torah today must be relevant to our lives today.

Judges are admonished that they must go after what they see before their eyes, they must take contemporary and community circumstances into account. If you go to an ultra-Orthodox rabbi, a Modern Orthodox rabbi, and a Conservative rabbi with a question about halacha, Jewish law, you very well may get three very different answers. This does not mean one is right and the others are wrong. Each goes after “what is before his eyes” and makes rulings that are right for their time and community. I find the level of hateful rhetoric between denominations very troubling because it is so unnecessary: we should be far more accommodating of the right of the individual rabbi, acting as mara d’atra, the halachic authority, for a community to make decisions for his or her community. We should follow the example of Hillel and Shammai and disagree with respect for the other’s position.

God doesn’t talk to us the way he talked to Moses. As Dr. House put it in the TV show, “You talk to God, you’re religious. God talks to you, you’re psychotic.”

The rabbis intentionally said the era of prophecy was over with Malachi. We can only speculate why – but I imagine it’s because they were aware of the danger that can come with people claiming to have a direct line to God. They can be dangerous fanatics.

When I make a ruling on halacha, Jewish law, I often have in the back of my mind the question, “what would God want?” And I think of the teaching in the Mishnah that says we should walk in God’s ways. Just as God feeds the hungry, we should feed the hungry. God visits the sick, we should visit the sick. God buries the dead, we should bury the dead. God wants us to be kind. As Hillel said, the rest is commentary, now go study the commentary.

Shabbat shalom