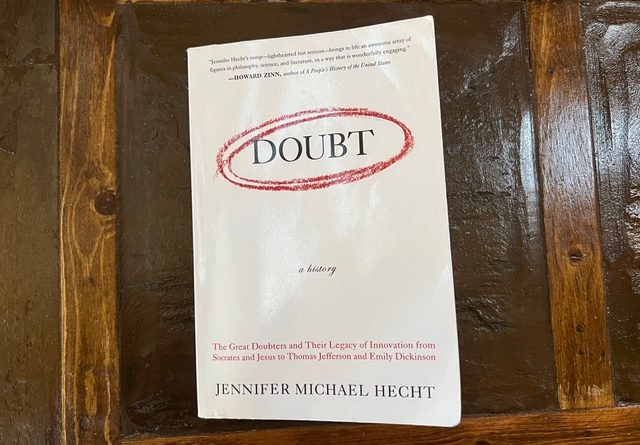

Review of “Doubt: a history” by Jennifer Michael Hecht

A book on religious doubt might seem an odd reading choice for a rabbi, a person almost by definition who is interested in faith.

But if your faith can’t stand up to intellectual challenges, it’s a pretty shallow faith. In the days of the rabbis 2,000 years ago, philosophy – and not just philosophy, but all “external writings” – was considered dangerous, and people were told it was forbidden to study them. There was good reason for their fear. We have the story of Rabbi Elisha ben Abuya, a.k.a. “Acher,” or “Other,” who started studying Greek philosophy and became a heretic, the only rabbi of the Sanhedrin, the “Jewish Supreme Court” of the day, known to do so. He famously said, “there is no justice and there is no judge.” In some ultra-Orthodox circles, studying such things is still considered forbidden, along with accessing the internet and exposing one’s self to anything that could challenge the beliefs of the community.

“Doubt: a history” is a brilliant introduction to the great doubters of history and includes figures both famous and obscure. The book opens with a “scale of doubt” questionnaire that invites readers to answer a series of questions to ascertain whether they are a believer, an atheist, or an agnostic. It was an interesting exercise to answer, although I do not think it is actually very useful or accurate. I consider myself a believer, although based on the “test results” I’m an agnostic. The theology Hecht uses to define believer is not the theology that I use to define believer.

But that small quibble aside, the book opens with the earliest Greek philosophers. Xenophanes of Colophon (570-475 BCE) is cited as the first known doubter, although there were no doubt many before. He doubted the Greek gods, feeling that the whole idea was “silly,” as not only did they act childishly, but they were very Greek. Xenophanes was known for “famously claiming that if oxen and horses and lions could paint, they would depict the gods in their own image.”

Xenophanes recognized that people create god in their own image. People believe the faith of the family and the community into which they are born. One of the Greeks pointed out that if he’d been born in India, he’d believe what the other Hindus believe. Does that make it right? Thinking you had the good luck to be born into the one true religion does not really make much sense.

A story from Diagoras brings another of my favorite challenges to faith:

…a friend pointed to an expensive display of votive gifts and said, “You think the gods have no care for man? Why, you can see from all these votive pictures here how many people have escaped the fury of storms at sea by praying to the gods who have brought them safe to harbor.” To which Diagoras replied, “Yes, indeed, but where are the pictures of all those who suffered shipwrecks and perished in the sea?”

Diagoras was pushing against what has been called the “God as Santa Claus model.” Just because you pray for something doesn’t mean God will give it to you.

Hecht walks us through the major approaches of the Greek philosophers, Plato, Aristotle, Epicurus, the Stoics, etc.

The book is organized roughly chronologically and by major region/faith. From the Greeks to the Jews. She sees Ecclesiastes and Job as the premier works of Jewish doubt. In the case of Job, God tells Job I’m beyond your comprehension, so shut up. In Ecclesiastes the author also says “we can’t know all these things,” it’s all vapor, so you might as well enjoy a good meal with a woman you love. Very Epicurean of the author.

The exhaustive book goes through Buddhist doubt, Roman doubt, Christian doubt, medieval doubt, the Inquisition, doubt in the White House, modern doubt. It really is quite an education. The author is both a respected historian and an award-winning poet, and it shows. The book has the depth you’d expect from a historian, with the attention to words and graceful writing you would expect of a poet.

Ecclesiastes and Epicurus are held as models of what she calls “graceful life philosophies.” Enjoying life does not mean neglecting family or community. You can be an atheist and still be a moral person.

In her concluding chapter she quotes Hume on the age-old question of theodicy:

Epicurus’ old questions are yet unanswered. Is He willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then is He impotent. Is He able, but not willing? Then is He malevolent. Is He both able and willing? Whence then is evil?

People of faith – which I think of as people belonging to a faith community, not necessarily people who blindly believe something – are able to adapt their beliefs as wisdom grows.

In his day, Spinoza was excommunicated as a heretic. Today there is a whole branch of Judaism, Reconstructionism, whose theology is very compatible with Spinoza’s ideas. Yesterday’s heretical idea is a foundation for today’s faith.

For doubters, Hecht’s book offers the consolation that “you are not alone.” You may not be part of a faith community, but you are part of a long tradition of doubters. She says, “to be a doubter is a great old allegiance, deserving quiet respect and open pride.”

The book also has value for “believers.” I suspect virtually every person of faith has had, at some point, a crisis of faith. Many religions, Judaism among them, celebrate doubt and encourage questioning. There’s a reason both Job and Ecclesiastes are in the canon. This book provides believers with many good questions to ponder.