Kol Nidre 5783 From Age-ing to Sage-ing

You’re going to die.

So am I.

So are all of us.

I realize this does not come as news to you. And yet, most of ignore this fact. We don’t like thinking about it, we don’t want to confront what that means for our lives or what, if anything, comes after.

People often report that after a near brush with death – surviving cancer or a bad car accident – they feel transformed, they find new meaning in many little things in life that they previously ignored.

The central message of Yom Kippur is really to give us that same kind of clarity without having to actually experience a near death experience. Because the truth is, none of us knows when we are going to die. Any one of us could die tonight.

A few months ago I went to Los Angeles to receive my honorary doctorate marking 20 years since I was ordained as a rabbi. The degree is a Doctor of Divinity degree, or D.D. We jokingly say those initials stand for “Didn’t Die” since that’s all you have to do to earn the degree. Sadly, one of my classmates was not there, because he did die. And he was the youngest person in the class, while I was the oldest. I’m the same age as his mother. Yet he was struck down in the prime of his life, with no warning, by a sudden and massive heart attack.

The advances of modern medicine means tragedies such as that one are rarer than they once were. Most of us will get to live into old age, and that presents us with a whole new set of challenges.

Like many people, ever since my 30th birthday I’ve marked the big “milestone birthdays,” the decades, with some kind of celebration. One year friends hosted a roast in my honor, another time we took a group out on a big sailboat on San Francisco Bay. It’s always been a fun time, but I have to say turning 60 was the first one that was difficult for me.

Those big birthdays are easier for men than for women. Turning 30 was great – I was already running a company I started, so being a little older did nothing but help my credibility. 40 is the alpha male age, and 50 is just “late alpha male.” But 60? That’s starting to get old. That was my grandfather’s age, it couldn’t possibly be my age.

Pirkei Avot even calls 60 the age of old age: It lists the stages of adulthood as follows:

At twenty for pursuit [of livelihood]; At thirty the peak of strength; At forty wisdom; At fifty able to give counsel; At sixty old age or being an elder; At seventy fullness of years; At eighty the age of added “strength”; At ninety a bent body; At one hundred, as good as dead and gone completely out of the world.

What, me? Hitting the age of ziknah, being an elder? But in addition to bewilderment at how fast the time goes by, I was also confronted with my mortality. Even if you somehow manage to get to the biblical 120, by the time you’re past 60 more of your life is behind you than in front of you. And for a few years you’ve been going to more funerals, and not only of truly elderly family members.

But in some ways it was more challenging to confront the idea of getting old than to confront the idea of dying. Our society offers no clear guidance for what to do with this chapter of life.

They say 60 is the new 40, because we’re living longer, healthier lives. But anyone who’s been laid off in their 50s and forced to find a new job, might tell you that as far as societal attitudes go, 40 is the new 60. Instead of being cherished as founts of wisdom with decades of experience, older prospective employees can be made to feel as if they are overqualified at best, and out of touch and irrelevant at worst.

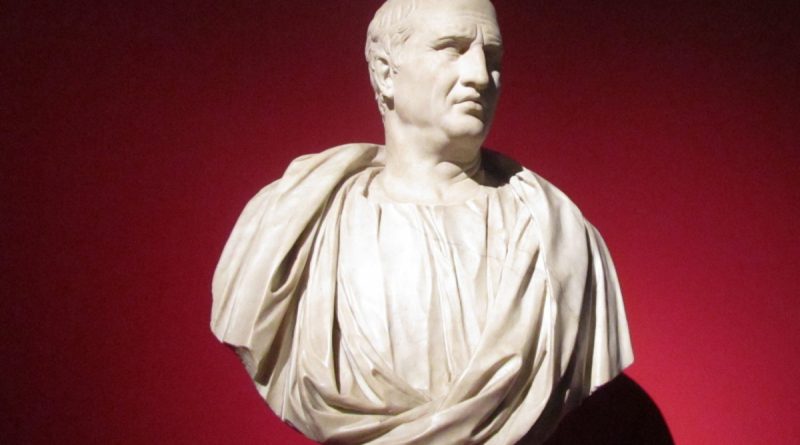

We often think that disdain for older people is a new phenomenon, that in the past the elderly were more respected. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Two thousand years ago, a couple of retired Roman consuls had two complaints about old age:

They were, first, that they had lost the pleasures of the senses, without which they did not regard life as life at all; and, secondly, that they were neglected by those from whom they had been used to receive attentions.

In other words, they didn’t enjoy eating, drinking, and sex as much as they once had, and they were treated as if they were no longer relevant.

What are we supposed to do at this stage of life? Suddenly go from running companies or having thriving law or medicine practices to playing golf, bridge, and going on cruises? Is that what the “golden years” are really all about?

With baby boomers now being senior citizens, we’re seeing more movies and TV shows with older actors. But what model for aging do they show? They joke about aging – Viagra and prostate issues for the men, toilets that rise up for women whose joints aren’t working so great. In the Kominsky Effect, starring Michael Douglas and Alan Arkin, Sandy is still teaching acting, and – season 3 spoiler – Norman dies in the saddle, still working as an agent. In Grace and Frankie with Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin, the lead characters are entrepreneurs starting new businesses and appearing on Shark Tank in their 80s.

In other words, if 60 is the new 40, just keep doing what you were doing when you were 40.

I love both of those shows – I appreciate the age appropriate jokes – but I think they both do a disservice to their aging cohort with their depiction of this stage of life.

What I’m going talk about this evening is that guidance that I felt was missing when I turned 60. As Rabbi Laura Geller said, “The norms, rules, and rituals of this stage haven’t yet been written; we are writing them together.”

Borrowing a term from Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, z”l, instead of age-ing, we could be sage-ing. Becoming sages.

Now I know we have an aging congregation, but not everyone here is over 60. You may be thinking, “I’m only 50 – or 40 – or 30 – or 20 – guess I can just tune out now.”

But this message is for you too. First of all, of course, you should be so lucky to live so long!

And as Cicero, a Roman statesman from over 2,000 years ago put it,

And yet that same failure of the bodily forces is more often brought about by the vices of youth than of old age; for a dissolute and intemperate youth hands down the body to old age in a worn-out state.

If you have any doubt about that, just take a look at Ozzy Osbourne. The life you lead and the decisions you make in your 20s and 30s will have an impact on the quality of your life in your 60s and 70s.

Rabbi Rachel Cowan wrote a book called “Wise Aging.” In it she wrote the stage of “late adulthood” is an opportunity for growth, discovery, and new meaning. She called it,

…an opportunity for us to do some of the most important inner work of our lives. During this stage of adulthood, we can live more deeply and turn away from superficiality. We are able to cultivate a deeper, more spiritual view of life.

I’ve been thinking about this for a while, and I’d like to offer four things to do or attitudes to have that lead to a fulfilling life in late adulthood.

- Acceptance

- Discovering the authentic self

- Nurturing relationships

- Integrating and sharing your life lessons

The first task is acceptance of our limitations, and the inevitable decline that comes with aging. Believe me, I can give testimony that no matter how much you run and workout, your body at 65 will not do the things it did at 35.

Ram Dass, one of the leading lights and gurus of the counterculture generation was born as Richard Alpert, an American Jew. He wrote a great book on aging called “Still Here,” a play on “Be Here Now” a book he wrote in 1971. In Still Here, Ram Dass describes his struggles with weight over the years, how he would swing between diets and gluttony, feelings of guilt and deprivation, telling himself he was too fat. Then he had an experience that changed all that. As he describes it,

I was teaching for a week at a Jewish family summer camp, and late one Friday afternoon, I joined all the men for a mikva, or purifying bath, that involved immersing ourselves in a hot tub and then a swimming pool, en masse, naked. There were men and boys of all ages, and looking around, I suddenly saw myself reflected in many of the bodies around me, descended, as I was, from Eastern European peasant stock. I saw in that moment that the contours of my natural body, which I’d been fighting most of my life, were genetically ordained! I felt my compulsion to be thinner start to shift, and soon my body weight had stabilized at 215 pounds with no diet involved. Statistics say that this is a bit too high, but I ceased caring, and shed the attachment to a thinner-body image.

But you have to be careful – there’s a fine line between acceptance and resignation.

Acceptance doesn’t mean just giving up. Acceptance means you do what you can with what you have, and adjust your goals accordingly.

I’ve been a runner for nearly 50 years. I’ve never been fast, but I enjoy challenging myself. When I was younger, I’d enter races chasing a PR, a personal record. I started running half marathons about ten years ago, and for a few years, my times got better as I was better trained, but then age took over. So my new goal was “age adjusted PR,” there’s a formula that can be used to “age normalize” your times. But nowadays I don’t want to risk injury, so I’m not even worried about an age adjusted PR. I ran the Montreal Half Marathon on Erev Rosh Hashanah and my goal was to have fun, challenge myself, and not get injured. I succeeded! If I tried to keep chasing even age adjusted PRs, I’d be at greater risk of injuries such as a pulled hamstring.

It’s a mistake to say, “I’m too old to do that.” Age is just a number. If your mind is still functioning well, it’s never too late to learn to use a computer, learn a new language, or pick up a new skill. The late Malcolm Forbes bragged about learning to ride a motorcycle at the age of 52. 52? That’s nothing. As long as you are in good condition, you can learn to ride a motorcycle or fly an airplane at 72, or older. Age alone doesn’t stop you from doing anything.

At the age of 100, Charlotte Sanddal is still busy chasing world records in swimming. She didn’t even start swimming seriously until she was 72, and now she can win medals just by getting out there and competing. Irene Hasserjian of Torrance, California, a retired flight attendant, recently took her first flying lesson at the age of 99.

As Cicero said,

Nor, again, do I now MISS THE BODILY STRENGTH OF A YOUNG MAN any more than as a young man I missed the strength of a bull or an elephant. You should use what you have, and whatever you may chance to be doing, do it with all your might.

The second principle is to discover your authentic self. For much of our lives, our authentic selves may be submerged. We may hide who we really are or how we really feel because we have a carefully cultivated image we share with the world, with our bosses, clients, colleagues. Or even congregants!

This is an extreme example, but I have a friend who is both a rabbi and psychotherapist, who helps Orthodox rabbis who have lost their faith in God and are no longer believers, but who are still working as rabbis, often because they don’t know how to do anything else.

For many older people, it comes naturally that we start caring less what other people think. This can make it harder to find a job as we get older. There’s a joke told about a guy in his 60s who wasn’t quite ready to retire, so he was interviewing for a new job. The interviewer asked him if he had any weaknesses. He said, “I’m too honest.” The interviewer said, “I don’t think of that as a weakness.” He replied, “I couldn’t care less what you think.”

But more than we hide our authentic self from others, we often hide it from ourselves. We often tell ourselves we are things, or we believe things because it’s what others expect of us, or because we convinced ourselves it’s who we should be, even if it’s not who we actually are. The starting point in the Netflix series Grace and Frankie is when two guys who’ve been friends for decades, started a law firm together, transition to retirement from the firm – and come out as gay, get divorced, and marry each other.

Discovering your authentic self sometimes requires effort and growth. Psychiatrist Daniel Siegel tells the story of a 93-year-old man who realized, rather late in life, that he was totally cut off from the world of feelings when he felt nothing when his long time business partner died. Even though he couldn’t imagine changing at his age, he wanted to be a better husband to his wife, so he worked with Dr. Siegel, using techniques including reflection and journaling, and learned how to connect with his feelings. His wife was so impressed she asked Dr. Siegel whether he had given her husband a brain transplant! Real growth is possible at any age.

A Chasidic rabbi, Reb Zusya, was on his death bed, and was feeling somewhat distraught. One of his students said, “But Reb Zusya, what are you worried about? You’re so great, you’re like Moses!” Reb Zusya responded, “I’m not afraid that God will ask why wasn’t I more like Moses. I’m afraid God will ask why wasn’t I more like Zusya!”

The third principle is nurturing relationships.

The High Holidays are all about mending broken relationships, and fixing damage we’ve done, asking for forgiveness.

But one of the biggest relationship problems people often find themselves facing as they get older is loneliness. We may have lots of friends in high school and college, and then find ourselves drifting away from our friends and being totally focused on our nuclear family during our prime days of raising a family and advancing in our careers. And then when we retire, and the kids are grown and living lives of their own, we feel the gap of a weak social network.

Choni the Circle Maker was a legendary rabbi who lived in northern Israel. He was widely revered for his wisdom, and he was on such intimate terms with God he could demand just the right amount of rain from God. He was an Israeli Rip Van Winkle – the Talmud tells us he fell asleep for 70 years, and when he woke up no one from his generation was left alive. People even ridiculed him for claiming to be Choni, since everyone assumed he’d died a long time ago. Feeling isolated, he prayed, “Either friendship or death.”

Whatever your age, treasure your friendships. Nurture your friendships. Everyone is busy, so you are probably the one who is going to have to pick up the phone and make a date to get together for coffee, a drink, golf, or a road trip. And it’s good to cultivate friendships with people of different ages, if you’re older, especially younger people. It’s beneficial for both.

And the last principle is integrating and sharing your life lessons. This is the “sage-ing” part.

Earlier I said Pirkei Avot calls 60 the age of being an elder. It’s the age for wisdom. Wisdom doesn’t just come from having intellectual knowledge. Wisdom comes when you have some intellectual knowledge and have been confronted with loss, conflict, and disappointment. If you’re willing to open your heart after you’ve been bruised by some of the things you’ve experienced, you just may be lucky enough to acquire some wisdom.

Martin Buber wrote that, “Every person born into this world represents something new, something that never existed before, something original and unique.… [T]here has never been someone like him in the world, for if there had been…there would be no need for him to be in the world. Every single person is a new thing in the world and is called upon to fulfill his particularity.”

If that statement is true at the start of life, it is all the more so true later in life, when each person’s unique experiences have further transformed that person into something original and unique. That original and unique wisdom that you have acquired it your personal Torah, and you really have a duty to share it.

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi said, “[Elders] are wisdom keepers who have an ongoing responsibility for maintaining society’s well-being and safeguarding the health of our ailing planet Earth.”

There are many ways you can share your wisdom. I’ve been working on a memoir. I’ve been working on it for over five years, and finally made some good progress and am about 90% done with my first draft. I don’t know if anyone other than my friends and family will read it, but I needed to write it.

You can write an ethical will.

You can just make it a point to share your stories and the lessons you’ve learned with your family and friends.

You can volunteer, or continue working in an emeritus capacity, serving as a mentor to younger colleagues.

There is, of course, also nothing wrong with continuing to work no matter how old you are if you love what you do. But it is important that even if you continue working, you make time for the essential tasks of late adulthood. Many of which are tasks that don’t have to wait until you’re in your 60s or beyond, because, as the High Holiday prayers remind us, none of knows how much time we have left on this planet. Who will live, and who will die.

I’ll close with some more advice from Cicero: “We must stand up against old age and make up for its drawbacks by taking pains. We must fight it as we should an illness. We must look after our health, use moderate exercise, take just enough food and drink to recruit, but not to overload, our strength. Nor is it the body alone that must be supported, but the intellect and soul much more.”

And that is excellent advice, regardless of whether you are 20 or 90.

G’mar chatimah tovah, may you be sealed for a good and blessed year.